The old woman said, "She was a beautiful girl, skin like porcelain, delicate and flawless, and she had a way of twisting her lips when she practiced. She was concentrating on the notes, you know. Cynthia Poulson was her full name, and I taught her piano. Every Tuesday afternoon, she came up to my flat, dressed in a navy jumper over a white blouse and white stockings—she attended The Dominican Sisters of the Perpetual Rosary—and she was in her tenth year. The wide collar of her blouse was absurd—I teased her by calling it a 'sick gull' with its splayed out wings—but Cynthia said, "Sister Marguerite says that the collar is meant to resemble the dove of the Holy Spirit, our white blouse and stockings are symbols of purity, and our navy jumper represents our commitment to our faith." I fancied the fabric of her jumper must be too rough for skin as soft as hers, but she never complained.

When I helped her pick her way through a new piece, I would place my hands over hers, so her fingers could find the right keys. Her fingers were as delicate as her features and small, almost too small to play fortissimo. When we played Beethoven for the first time, I feared I would break them. Even now, I can feel her soft hands beneath my own and smell her lilac scent and hear her say, 'Please, Miss Wallace; I can do this by myself!' Then she would twist her lips and touch the keys, but tentatively as if they might move away from her. Her favorite piece was Clair de Lune. Once she told me, 'Miss Wallace, if I were to only learn this one piece, all our lessons would not have been in vain, and I would be happy.'

And I said, 'Miss Poulson, nothing done in love is ever in vain.'

Then one day—it was a cold gray day in November, 1888, and a sharp wind was blowing from the Upper Bay—she began playing, and something happened, that indefinable moment when a spirit outside ourselves takes over, and the heart and belly and viscera find themselves inside the music; Cynthia's delicate fingers found the keys, found them with certainty and passion and adoration, and her lips were smiling and her eyes were closed, and I felt a surge of love I had never felt before, and when the last chords faded into the shadows of my room, I turned her face to mine and kissed her. For a moment she pulled away, her eyes wide and full of tears, but then she leaned toward me and kissed me back, and I was filled with an unimaginable joy. From that moment on, our love grew stronger and more passionate, and we shared everything: our hearts, our music, our bodies, our deepest dreams. For over a year, Tuesdays were my Sabbath, a day of worship and rest, and hers, too, or so I thought.

In April of 1890 she told me that she was going to a women's college in Vermont. She said her parents wanted her to study literature, so she could be a teacher, but she promised she would continue playing the piano. "Nothing done in love is ever in vain; isn't that what you said?"

Of course, I was frantic. I felt as if a beautiful young tree had been planted in my heart and just as it was beginning to bloom, it was being torn up by the root ball. As if the sapling was tearing itself from within me. I cried out, "But what shall I do without you? You are everything to me!"

She promised she would come back and see me, that we would still be friends and play the piano together. But I could see the future! Some young man from a brother college—a fraternity man with strong features and a wool suit would make her his own, and I would be forgotten except as a wayward misadventure of youth. And I saw with equal clarity, that is what her parents wanted. Did they suspect our forbidden love? Or was their plan simply to pursue the natural order of things?

So, I said, 'Let's go away! Together, where we won't be found! We'll create a life for ourselves.'

And she said, 'Jean, no. We can't go on this way. You know we can't! Your reputation would be sullied forever, and no one would ever come to you for lessons again. And what would happen to me? Am I to live out my life as an old maid in a relationship condemned by both church and society?'

I replied with similar ardor, 'But that's why we'll leave! We'll go where there is neither church nor society! Into the deep woods. Yes, you and I. And our love will never die.'

I could feel her resolve weaken, and so I painted a picture, one rather like Debussy might fashion in music, but not with notes, with words lilting and plangent, words rising and falling in diminuendo and crescendo, wild implausible poetry that painted beautiful tomorrows until she saw us walking hand in hand in through forest glades with the sun squinting through green leaves and sleeping in one another's arms while moonlight bathed our bodies. I created a dream, and she struggled to believe that dream, wrestled in her imagination with various visions of her future until she conceded that, yes, she and I could be happy forever!

Every day for a full month, I visited the Astor Library and pored over newspapers and circulars and magazines of all sorts until I found a plausible Eden: the deep clefts of the Ozark Mountains and a magical spring—or so ran the ad—called Roaring River. Of course, she couldn't tell her parents or anyone else we were 'running off' together. That would have created a scandal beyond any redemption. So Cynthia came up with a simple plan: She would ask her parents for a 'graduation trip' to New Orleans to learn about a new musical genre, jazz, and a black musician named Buddy Bolden who was changing everything, and she suggested that I could be her chaperone, so the four of us met in the Poulsons' parlor, and Mr. Poulson gave us his blessing.

Cynthia didn't stay in the Ozarks long. The heat that June was oppressive, and though we had a decent log cabin, she longed for the more comfortable city and the arts and the crowds. She grew to hate the isolation of the deep woods, and I realized that I had built too large a dream on too small a foundation: To possess each other on Tuesdays may have seemed like heaven, but I was not enough to fill the other six days. Cynthia grew listless and irritable and finally, she said, 'Jean, I'm going. I don't like it here. I want to go home.' I asked her what she would say about New Orleans, and she said, 'I lied to come here, and I'll lie when I get back. If you've taught me nothing else, you taught me how to lie.'

All I could think to say was, 'Oh.'

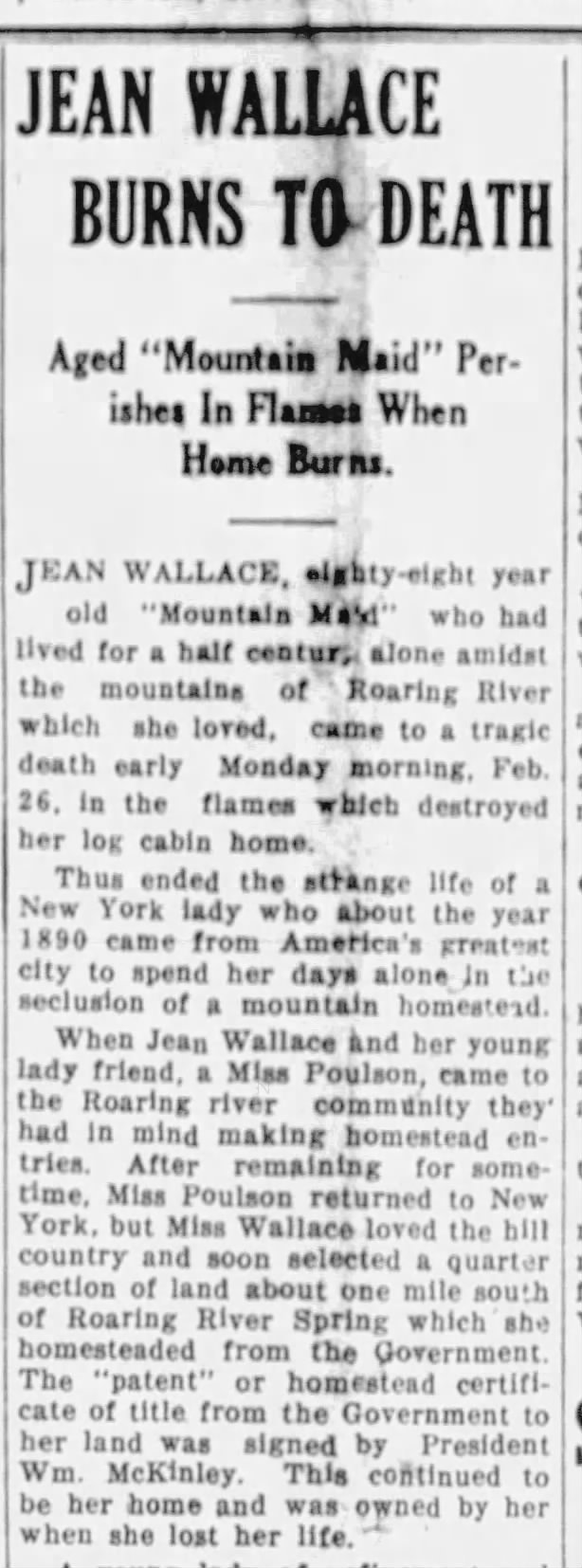

O—the symbol of nothing. No words, no dream, nothing. No love. She returned to New York in time to celebrate the Fourth of July, and I never heard from her or of her again. And that's how I came to be here. Alone. Friendless. The Mountain Maid of the Ozarks. Even in death I am a fool, and I still hope to see her face silvered in moonlight. But she will never come again, and in the paradox of time, I who lost everything am asked to find missing trifles: rings and manuscripts and gold coins."

The apparition began to weep softly, and with a timid gesture, I touched her sleeve.