Chapter Eighteen

What Really Happened in Charleston Continued / The Fissure King

Many a Ouija board has been burned in the fireplace after some girl and her best friend, Julie, asked about their future husbands, and the Ouija spelled out, "Darl Hitchens" or "Auggie Finch" or some other local, handsome lad. The girls giggled and kept asking questions, until the board turned mean and treacherous and identified itself as Lucifer or Count Vampiro or some other wicked character whereupon the girls shrieked in terror, snatched up the board, tried to break it, failed to break it, and so threw it in the fire. The girls, according to their story, were still quaking with fear when they heard a demon howling blasphemies from the fire. Years later, the girls would tell the story and say, "The board told us things we had no way of knowing." The truth, of course, is less dramatic; the girls simply didn't know themselves as well as they thought, and deep in the dreaming dark of their unconscious minds was a storeroom of unremembered names and nightmares that were admitted to the neocortex through the agency of the Ouija board.

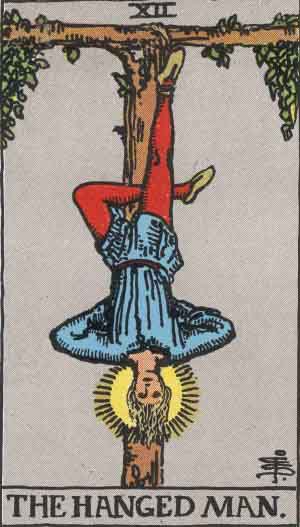

Tarot cards work similarly. The illustrations and symbols, some of them adroitly hidden in the folds of garments or the shadows of landscapes, work on the imagination and create a passage for the repressed past to emerge. We skeptics know these things–until they happen to us. When we're the ones touching the planchette or flipping the cards or sticking our finger at random in the Bible, the experience we deride in others as rank superstition becomes irrefutably significant to us.

We can't help it. The distance between who we are and who we think we are basically corresponds to the distance from the earth to the moon. The distance between our conscious and unconscious minds is almost exactly 93 million miles. That's quite a coincidence when you think about it.

The Feast of the Epiphany–Old Christmas for the Amish and a few recalcitrant Irish (well, all Irish are recalcitrant, but only a few of them celebrated Old Christmas)–was over and done. The cattle had arisen from kneeling and were contentedly chewing hay from a manger in the barn. The Wise Men had gone home by a different way, and Baby Jesus was cooing in the crib with little chunks of myrrh and frankincense sticking to his tiny fingers. The gold ingot he ignored altogether. In the apartment at 364 King Street, however, a more ominous scene was unfolding. Once again, the curtains had been drawn, the room darkened, and a familiar skull grinned from the center of the dining room table; Maggie Fox had gently placed it there on a lavender doily as if it had been the decapitated head of King Charles the First—Bad Luck Chuck to his detractors—or Marie Antoinette—a silly girl deprived of the capacity to offer cake to anyone. The skull was flanked fore and aft by two silver three-stemmed candelabras. Five of the six flames were jittering and puffing little wreaths of smoke while the flame of one candle was as rigid as a golden teardrop. Spinster Mincy, powdered and rouged to resemble Ligeia from the sepulcher, had taken her place at the head of the table, and she looked straight ahead with an air of grim and thin-lipped sagacity. (As mentioned before, she was a wily old woman and knew what she was about.) On her left were T. Allen McQuary and Maggie Fox, and to her right were her niece Melinda Mincy and Kate Fox. At the far end of the table sat a young man whose oily hair dangled in his eyes. He returned the Spinster's gaze with the slightest of nods, whereupon she began, "We are gratified by the presence of each of you today. I would like to introduce our guest, Mr. McQuary."

"Thank you for having me." Mack was decked in purple, of course, but his chapeaux hung on the hat tree by the door. He and the younger Melinda Mincy avoided one another's eyes lest they betray themselves.

The Spinster asked, "You have met the Fox sisters, I presume?"

"Yes, Mrs. Mincy. We had a very cordial conversation, thank you."

"Miss Mincy, if you please. And you have made the acquaintance of my niece?"

"I'm delighted to say we met in passing at the country club." Mack and Melinda exchanged cautious smiles. "Even with so brief an introduction, I could tell she is a most remarkable young lady."

"Indeed," said the Spinster. "She is a talented girl, or so I've heard. And have you met Mr. Augustus Victor? He writes for The News and Courier, and he is both open-minded and judicious. Augustus, thank you for joining us."

Mack replied, "Mr. Victor interviewed me soon after my arrival in Charleston. He has an admirable regard for the truth."

"A journalist's only virtue is his devotion to the truth, Mr. McQuary."

Oily bastard, Mack thought. Wonder what's up his sleeve? For that matter, I wonder what the old bat is up to?

Augustus said to the Spinster, "Miss Melinda, I thank you for inviting me. I have long desired to participate in a seance. And I assure you, ladies"–and here he addressed the Fox sisters–"I do not prejudge anyone or any experience. I approach everything with, in Keats' memorable words, a 'willing suspension of disbelief' so that by abeyance I might discover the truth. Fairness and objectivity are the journalist's best tools."

Mack coughed and cleared his throat.

"Mr. McQuary?" the Spinster asked, "are you quite all right?" Before Mack could answer, she called to the kitchen door, "Ruby? Would you bring Mr. McQuary some brandy for his throat?"

"Yes'm," said a voice from the kitchen, and a moment later, the old black woman bustled through the door with a snifter of brandy. Mack quaffed the drink and replaced the glass on the tray. "Thank you, Ruby," he said. "Much better."

"Very well, then," the Spinster said, and she nodded to Maggie. "Miss Fox, would you please tell us what to expect from your conjurations?"

"Yes, Miss Mincy. My sister and I had the pleasure of conducting a seance here just two days ago. In the course of our spirit communications, we met Colonel William Mincy."

The Spinster interrupted. "It was a joy and consolation to speak with Father, and it comforts me to know he is at peace. I am most grateful to you and your sister."

In a convincingly sad voice, Melinda said, "I never knew my grandfather. He passed before I was born. But I have heard stories of his generosity and gallantry."

The Spinster reproved the girl. "He didn't 'pass,' my dear; your grandfather's death was no straw death. He died defending our beloved South, and his last gesture on this earth was to kiss the bloody blade of his sword, and his final words were, 'God damn all Yankees to hell!'"

Good God! thought Mack. I'd better tread carefully with these folks.

"Sorry, Aunt Melinda. I did not intend to slight grandfather's honor."

"Of course not, my child."

Maggie continued, "Melinda, your grandfather was particularly concerned about you."

Melinda said, "About me? Why? What did he say?"

Kate rolled her woeful eyes upward and said, "He is worried about your soul."

"My soul? What about my soul?"

"He said a dark and moonless night was coming to destroy your soul, but beyond that, he said nothing. That is why we are here."

Mack thought, Wait a minute! That sounds like too much of a coincidence—"dark and moonless night." Better tread carefully!

But Maggie had begun rocking back and forth in her chair ,and now she was moaning, "Ooooh! Oh, come! Come to us, Colonel William Mincy! From beyond the sepulcher, beyond the veil, beyond the silver, twinkling stars!" She quivered and shivered and sweat exuded from her brow. For the first time since they met, Mack felt himself attracted to her passionate presence. Perhaps it was the sweat.

Then, from beneath the table, a resounding crack.

Maggie whispered, "Sshh! He is with us! I feel his presence! William Mincy is here. Behold!" With her dark eyes wide and staring, she lifted her hands toward the skull. From the eye sockets and nose cavity rose thin spirals of smoke that merged sensuously into a vague figure, a shadowy and writhing homunculus. At once, the table jerked toward the younger Miss Mincy, and one corner rose, albeit slightly. A whisper of a breeze swept over the table, and the candle flames flickered and jumped, whereupon the eyes of the skull poured out thick streams of smoke that smelled of cedar and middle eastern herbs. Mack glanced at the Fox sisters, but neither of them had changed her expression or seemed to be exerting herself. In fact, Kate's eyes had become sleepy as if she had lapsed into a trance, and Mack thought, Damn, these girls are good. Watch and learn, buddy boy.

As if she had heard a voice, Maggie intoned, "Yes, Colonel Mincy. We will enable you to speak to your granddaughter."

From a valise, Kate produced a large scroll of paper and planchette, and she set them on the table. Then she twisted a pencil into the hole. Meanwhile the smoke from the skull hung over the table and veiled the faces of the sitters. In a quiet but confident voice, Kate asked, "Mr. Mincy? Through which vessels do you wish to flow? Please, knock once for your daughter, two for your granddaughter, three for Mr. McQuary, or four for Mr. Victor." Three distinct cracks sounded beneath the table.

I shoulda known, Mack thought. Here we go.

A pause and then a single loud knock. The Spinster turned to Mack with contempt glittering in her eyes, and he flinched.

Damn, what crawled up her ass? The old bat heard must've heard about my fadoodling her niece. Well, that maiden lost her head a long time before I got here. He glanced at the girl and remembered her succor and how good it felt and hoped she would succor him again soon.

But he turned to the Spinster and said, "And so, Miss Mincy, you and I have been chosen as communicants. I am honored to share this moment with you." The sepulchral old woman nodded her head, and Mack thought, I have a feeling things are about to get weird.

Maggie slid the paper and planchette to the corner between Mack and the Spinster and said, "The two of you place your fingers on the planchette. No, Mr. McQuary, not like that. Touch the edge with your fingertips. Good. Now close your eyes, and do not open them." Then in a loud voice, "Colonel Mincy! Speak to us!"

The Spinster and Mack sat with their eyes closed and their fingertips on the planchette; they looked as if they might be praying to a pagan idol. The skull's eyes were smoking and the candle flames were fluttering, and the fascination of the others showed they anticipated something, something mystical and meaningful and perhaps demoniac. Then, with an abrupt jerk, the planchette began to move; it swept over the paper in a wide arc, and in the upper left corner scrolled forward in elegant cursive: "Beware . . . dark. . . knight. He. . . is. . . f-r-a-u-" Mack peeked to see what was being written and observed the Spinster's eyes gleaming beneath her lashes.

Ah, so that's her trick! Well, two can play at this game.

Meanwhile Augustus Victor had risen from the end of the table and was now leaning over the Spinster's shoulder to watch the planchette inscribe Mack's condemnation. Under his breath, Augustus announced, "The truth appears!"

Abruptly and in mid-word, the planchette paused. When it resumed, the planchette wrote, "is f-r-a-u-g-h-t with care for . . ." And the planchette stopped again. Mack glanced up, and the Spinster was openly glaring at him. He felt the planchette pressing against his fingers, and it began to write, "nothing but his own p-l-e-a-s…"

Read this, you old bitch!

Mack pushed the planchette hard against the Spinster's fingers, and it wrote out, "nothing but his own pleasing God."

That'll have to do under the circumstances.

The planchette stopped, and Maggie intoned again, "The syntax is broken and the meaning unclear. Colonel Mincy, tell us clearly what you wish to say!"

But the Spinster and Mack were both pressing hard against the planchette, one struggling to indict and the other to defend. Suddenly, the planchette popped from their fingers, flipped a couple times, and landed pencil point down on the paper. The old woman peeled back her lips and bared her teeth, and Mack flinched.

Holy shit!

And that's when something happened no one expected, not even the Fox sisters, not even Augustus in collusion with the old woman by whose shoulder he stood, not even Mack. The planchette began writing on its own. In large block letters, it scrawled out the words: "Ha, ha, ha! Bunch of liars!!" The sitters watched in frozen fear as the planchette scratched an exclamation points in the paper and spiraled tightly to create dots. Augustus knelt and looked under the table for a magnet or some kind of mechanical device but saw nothing suspicious except the naked right foot of the younger Melinda. When he bobbed up, he said to the sitters, "There's nothing. What can this mean?"

The younger Miss Mincy said, "It means we're all fakes, you idiot. What else can it mean? And, by the way, that includes you, too!" She knew that Augustus wanted her, but she refused him because she hated his oily hair and radical politics and sanctimonious attitude.

"That's not true!" he said. "I am not a liar! I want only the truth!"

The planchette spelled out, "Horse shit."

Then Mack called out, "Look to Kate, Melinda!" Pale and trembling, Kate had fallen into a hypnotic trance or apoplectic seizure, and her eyes were all whites, and flecks of spittle were on her lips, and she was slumping from her chair toward Melinda, who caught the girl and laid her head in her lap.

Across the table, Maggie Fox leapt from her chair and shrieked, "Kate! My dear sister! Yes, it's true: We're toe-cracking, table pushing frauds! But it's all Leah's fault! She turned us into liars! Liars and frauds! I confess it to you all!"

Augustus hurried to his chair and began scribbling furiously on his pad.

The planchette scrawled out, "Told you so. What about you, purple boy?" The planchette paused and then spelled, "Well?"

Mack felt as if he were splintering, as if the hemispheres of his brain had been severed, and disparate memories were issuing from the cleft. He heard his mother's voice in the kitchen: "You're your own worst enemy," and his smug reply, "Well, then I have nothing to worry about." He heard his father whistling How Great Thou Art, and he felt the polished wheel of the Prouty in his hands. He smelled solvents and oils and vinegary wood pulp. He saw a small man with a preposterous mustache and top hat pull himself out of the chasm and stand unsteadily on the left hemisphere whence he pointed his finger at Mack and said, "Repent and turn away from lies!" Mack saw himself standing on the right hemisphere, and he asked the top-hatted man, "Who the hell are you?" The little man said, "I am Bulfinch, and I will bring you to your knees!" Then M.S. Glenn, his trusted friend and partner in chicanery, climbed out of the crevice and stood beside Bulfinch and said, "Don't listen to him, Mack! He's got nothing. You and I are driving this narrative, no one else." Then, who should crawl out next to join Bulfinch and Glenn but Hennessey? As usual, he didn't say anything. He just stood there looking debonair and sucking on a stick of peppermint.

But, mostly, Mack saw girls, supple and willing and wide-eyed with innocent admiration. They were parading about, some in their knickers, some in their shifts, and some in nothing at all. With the desperate passion of a young man skulking in the narthex, he desired the girls more than anything, but they were on the other side of the Great Divide and apparently, couldn't see him. They were blind to his presence! So they gathered around Hennessey—the handsome dog—and he was smiling and giving them candy. One girl removed his hat and tousled his hair, and another ran her hands over his chest and under his jacket and another kissed his freshly peppered cheek. Mack saw Melinda Mincy climb from the crevice, and she began succoring Hennessey, and Mack cried out with jealous rage, "Stop it! Stop!" But the girls couldn't hear him, and he realized that even if they did, they wouldn't care. He clapped his hands to the sides of his head as if he were trying to press the hemispheres back together, to squeeze his cloven skull into one globe, to force the emerging images back into the fissure, back into the darkness whence they appeared.

Listen, for herein lies a truth: A man may hold a whiskey glass up to the westering sun and observe a prismatic rainbow in the thick contours of the glass. He may remark on the beauty of the glinting light and the fresh beads of water trickling down the sides. And he may with certainty call it art.

But death also has a ray of westering darkness, a shard of jet that slices the consciousness into futile fantasies and bleak memories, moods of defiance and calm despair, quests into the caves of nothingness. That's mortality for you! Of course, the beam of death creates no prismatic rainbow, for it has no light, only lignite, compressed and adamantine and inky-black, sharp like a blade and smelling like a grave. And when the consciousness is separated into lies and lusts and the futile photographs of loved ones long dead, a drama occurs on a stage far, far below the balcony whence the greater Consciousness speculates on the vain gesticulations of pallid actors. What to do with this drama? How to interpret?

Mack was pondering these questions when he heard the chuckling chortle of a child. He looked over Melinda's left shoulder—and a pretty shoulder, too, round and smooth when the gown slips off—and he saw a small boy hovering in the corner, a child of maybe five or six, dressed in a yellow nightshirt and bald as a gourd. The boy had an uncanny smile and protruding ears like those of a baby hippo. Mack said in a horrified whisper, "Oh, my God. Billy Simpkins! What are you doing here? Why are you here?"

Melinda spoke sternly, "Mack, stop it! Stop it! Look at me. Look at me! Who are you talking to?"

Vague and distracted, Mack said, "He's behind you, Melinda. Over your shoulder. No, no. Up higher. See? Close to the ceiling. It's the ghost of Billy Simpkins. See?"

Melinda looked over her shoulder. Now in a fierce voice, "I don't see anything. What do you see?"

"Look!" Mack pointed to the dark vacancy.

The Spinster rose from her seat and said, "I've had enough of this. I'm tired now. I must go to–" And even as she was excusing herself from the company she herself had convened, she collapsed. The planchette scuttled out of the way and so avoided the thump of the old woman's head hitting the table. Miss Melinda screamed—"Auntie!"—Maggie sobbed—"We're frauds!"—Kate slept—"Zzzz"—and Augustus Victor scribbled madly in his book.

But the boy in the yellow nightshirt said nothing. He just smiled and hovered and was gone. The planchette began to move again. "Hey, Mack! See you in the funny papers!" it wrote.