Chapter Eight: Historical Notes

The Zoo Park Send-Off

The Real T. Allen McQuary

Thomas Allen McQuary was a real person who, on July 4, 1897, embarked on one of the most audacious publicity stunts of the late 19th century. This wasn't fiction—it was a carefully orchestrated spectacle that captured the imagination of newspaper readers across America.

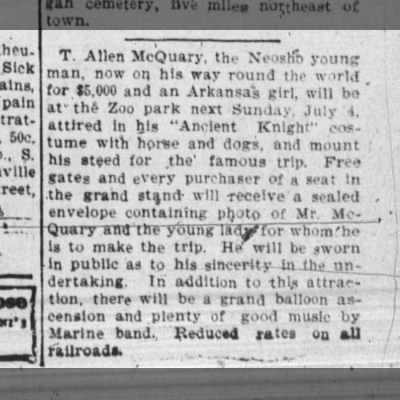

The Young Man from Neosho

McQuary hailed from Neosho, Missouri, a small town in the southwestern part of the state. At the time of his departure, he was described in newspaper accounts as a "young man" setting out on an incredible journey that would allegedly take him around the entire world.

What made his quest remarkable wasn't just the ambition—it was the theatrical nature of it all. He was to travel in the costume of an "Ancient Knight," complete with a black or purple plush outfit, a black mask, a blade, and accompanied by a black horse and two greyhounds.

The stated reason for this extraordinary journey? The hand of an unnamed Arkansas girl and a prize of $5,000, pledged by her father—a wealthy planter who had supposedly set these impossible conditions for any suitor who wished to marry his daughter.

Contemporary newspaper coverage of McQuary's send-off at Zoo Park

The Terms of the Quest

The conditions of McQuary's journey were published in newspapers and read aloud at his send-off ceremony. They were remarkably specific and designed to capture public attention:

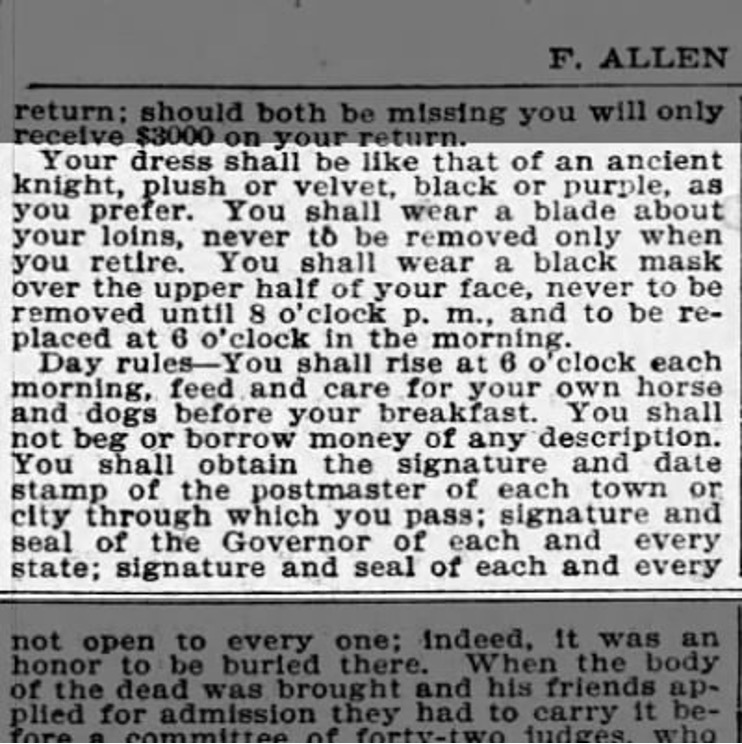

The Oath and Requirements

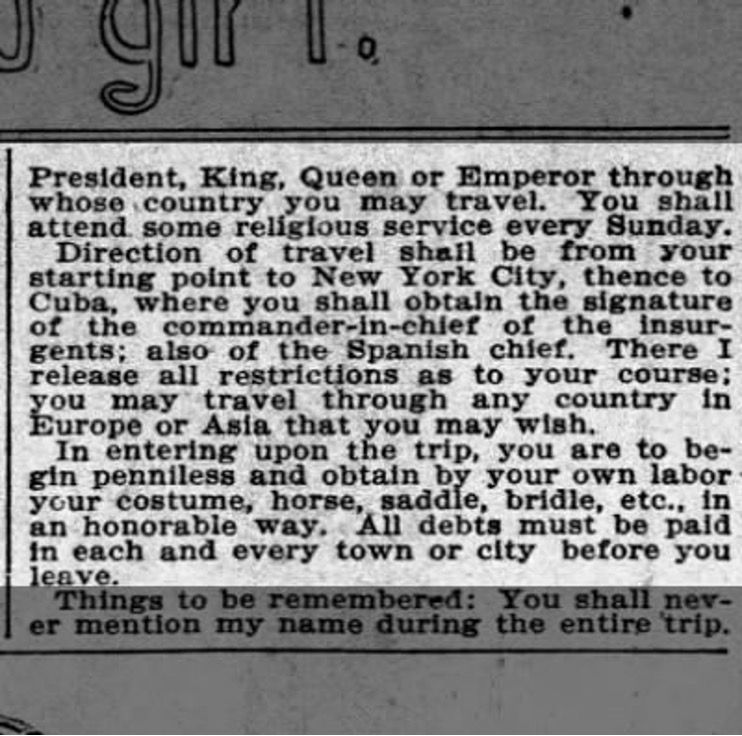

The Route: McQuary was to travel from his starting point to New York City, then to Cuba, and from there through any countries in Europe or Asia he wished before returning home.

The Time Limit: He had exactly 18 months to circumnavigate the world and return.

The Starting Condition: He was to begin penniless—absolutely no money on his person. He had to earn everything he needed through "honorable" labor along the way.

Documentation Requirements: He was required to obtain the signature and date stamp of the postmaster in every town or city through which he passed, the signature and seal of the Governor of every state, and the signature and seal of each President, King, Queen, or Emperor of every country he traveled through.

Religious Observance: He was required to attend some religious service every Sunday, regardless of where in the world he found himself.

The Costume: He was to wear his "Ancient Knight" garb in black or purple plush or velvet, carry a blade about his loins, and wear a black mask over the upper half of his face from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. daily, which could only be removed at 6 o'clock in the morning.

The Secrecy: Most importantly, he was forbidden from ever revealing the name of the Arkansas planter or his daughter throughout the entire journey.

The elaborate terms of McQuary's oath, as published in contemporary newspapers

Further details of the journey's requirements and restrictions

The Zoo Park Send-Off

On Sunday, July 4, 1897, McQuary's send-off took place at Zoo Park in Springfield, Missouri. This was actually the Interstate Fair Association and Zoological Gardens, established in 1894 on land that would later become Dickerson Park Zoo.

The Venue

The Interstate Fair Association grounds featured a large grandstand (amphitheater) that overlooked a racetrack. This made it an ideal venue for public spectacles, exhibitions, and events. By choosing the Fourth of July—America's Independence Day—the organizers ensured maximum attendance and patriotic fervor.

The grandstand could accommodate hundreds of spectators, and the event was promoted with promises of "grand balloon ascension" and "plenty of good music by Marine band." Railroad companies even offered reduced rates to encourage attendance from surrounding areas.

The grandstand at Zoo Park where McQuary's send-off ceremony took place

The event featured a formal oath-taking ceremony, with McQuary placing his hand on a Bible and swearing to uphold all the conditions of his quest. Attendees who purchased seats in the grandstand received sealed envelopes containing photographs—likely of McQuary himself, or perhaps of the mysterious Arkansas girl he claimed to be pursuing.

The ceremony was designed as spectacle: a young man in theatrical costume, taking a solemn oath before hundreds of witnesses, promising to embark on an impossible journey for love and money. It was part revival meeting, part circus, part romantic melodrama—everything that late 19th-century America loved.

The Nature of the Spectacle

Modern readers might wonder: was any of this real? The answer is complicated.

1890s Publicity Culture

The 1890s was the golden age of publicity stunts, promotional schemes, and what we might today call "performance art" masquerading as genuine endeavor. Newspapers were hungry for sensational stories, and promoters knew that an ongoing narrative—especially one involving romance, adventure, and mystery—could sell papers for months.

Around-the-world quests, races, and challenges were extremely popular. Journalists traveled around the world trying to beat Phileas Fogg's fictional record. Daredevils attempted impossible journeys. Reformers made pilgrimages. And hucksters concocted elaborate schemes that were part genuine adventure and part theatrical fraud.

McQuary's quest had all the hallmarks of a carefully constructed publicity scheme: the mysterious Arkansas girl whose name could never be revealed (convenient for avoiding verification), the theatrical costume (guaranteed to attract attention and newspaper coverage), the elaborate requirements (each one a potential news story), and the involvement of what appears to be a promoter—M.S. Glenn—who saw an opportunity to profit from the spectacle.

Whether McQuary truly believed he would complete his quest, whether there ever was an Arkansas girl and her wealthy father, or whether the entire enterprise was conceived from the beginning as a money-making scheme, we may never know with certainty. What we do know is that hundreds of people gathered on that Fourth of July to witness his departure, newspapers covered the story, and for a brief moment, T. Allen McQuary was famous.

The Reporters: Bulfinch and Hennessey

The characters of Otis Bulfinch and Van Hennessey—the two reporters depicted in this chapter—represent the dual nature of newspaper coverage in this era. Some reporters were skeptics who sought to expose frauds and hoaxes, while others were willing participants in promotional schemes, understanding that sensational stories sold papers regardless of their veracity.

The tension between these two approaches—journalistic integrity versus commercial success—was very real in 1890s newspapers. Many publications ran both exposés of frauds and promotional coverage of obvious hoaxes, sometimes even in the same edition.

What Happened Next?

The story of what actually happened to T. Allen McQuary after his dramatic send-off is one that will unfold in subsequent chapters. Suffice it to say that reality, ambition, and human nature would all play their parts in determining whether the Purple Knight's quest ended in triumph, tragedy, or something far more complicated.

What makes this story particularly fascinating is that it's real—or at least, it began as something real. A young man really did set out on this journey. Newspapers really did cover it. People really did gather to watch him depart. Whether what followed was heroic adventure or elaborate con game (or perhaps both simultaneously) is the question that drives this narrative forward.

Sources and Documentation

The details in this chapter are drawn from contemporary newspaper accounts, promotional materials, and historical records from Springfield and Neosho, Missouri. The newspaper clippings reproduced in the chapter are authentic documents from 1897, providing firsthand accounts of McQuary's send-off and the terms of his quest.

The Interstate Fair Association and Zoological Gardens (Zoo Park) site eventually became Dickerson Park Zoo in 1923, though the original grandstand and fair buildings no longer exist.