Chapter Two

A Fun and Educational Excursus on Journalism in 1897

In the dwindling years of the Nineteenth Century, people submitted their own jibber-jabber to their local newspapers, which meant that many smaller papers like The Neosho Rustler needed only one reporter, which in the case of the Rustler was Mack. He would go out and interview someone whose home had burned or whose child was killed in a farm accident or who had been bamboozled by some big talking grifter. But usually people just slid their stuff through the slot in the door and waited for the paper to come out. Every Monday and Wednesday, Mack had to edit the jibber-jabber before laying out the paper and setting the type. He excelled at these tasks even as he hated performing them. But he was cursed to know the difference between "lie" and "lay" and "their" and "they're" (and "there") and when to use a semicolon; he knew to insert commas before coordinating conjunctions. He knew the difference between the indicative and conditional moods and how to use relative pronouns. He could transform a syntactical nightmare into eloquent prose. Mack was a hell of an editor, but editing to Mack was hell, and he often thought, "Maybe if I got out of Neosho, I could write like Twain or even Verne. It's this goddamn town that's holding me back."

For the time being, however, the "goddamn town" was keeping the McQuary family in butter and biscuits, so Mack had to "work his magic," as his father called it, on the jibber-jabber and make it coherent.

As a practical matter, A.L. also instructed Mack in the commercial side of the newspaper business. Subscriptions have never covered the cost of publishing a newspaper, any newspaper ever, so advertisements have always been necessary for papers to stay afloat. Some ads were "true" and others "false" (such is still the case) and the Neosho Rustler ran both: "false" ads for medicines that cured no ills and hair ointments that grew no hair, but also "true" ads for meat grinders, gingham, and plows. The ads for land "as pristine as Eden" and for mules with all their teeth might be true or they might not—caveat emptor!—while the ads for brush arbor revivalists and the Chautauqua were irremediably ambiguous. As A.L. often said: "You can't run a paper without money, and you can't make money without ads. We hope the advertisers are telling the truth, but that's on their conscience not ours. I don't have the time or inclination to try every patent medicine that pays us to advertise."

So it is that truth and bullshit have ever dwell in cozy proximity and will continue so to the ending of the age.

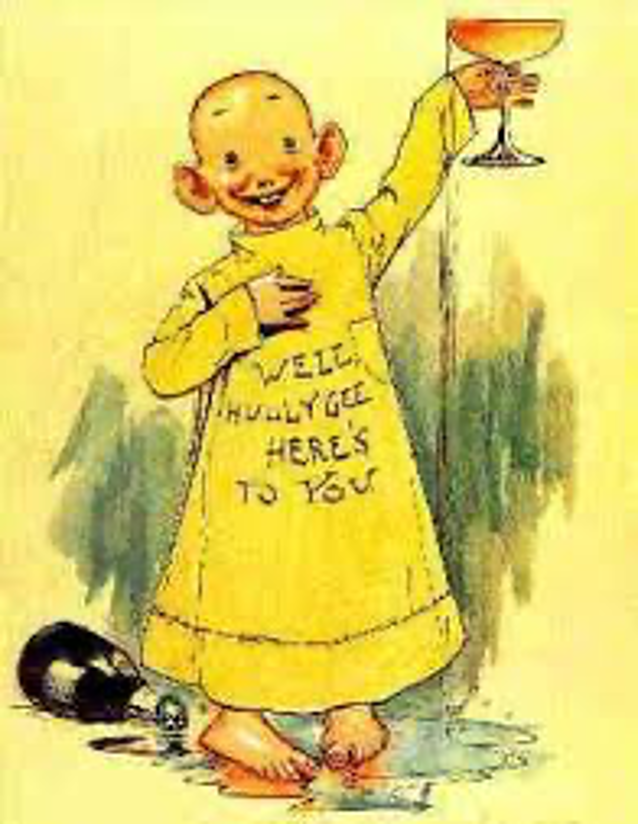

Then in 1895 something happened that shook the newspaper industry to its roots, a development so absurd and unlikely that it challenged the staid and reliable principles of journalism: Joseph Pulitzer introduced a comic strip called "Hogan's Alley" into the New York World. The strip was written and illustrated by Richard Outcault and featured an ugly, bald-headed kid in a yellow nightshirt. The kid was named Mickey Dugan but nicknamed, appropriately enough, "the Yellow Kid," and "Hogan's Alley" became enormously, outrageously, and disproportionately successful.

The popularity of "Hogan's Alley" resulted in an upsurge in subscriptions to the World that in turn attracted more advertisers who were willing to pay more money for ad space. The influx of cash ramped up an already fierce rivalry between Joseph Pulitzer and William Hearst. Hearst hired Outcault away from Pulitzer. Pulitzer responded by hiring George Luks to write his own version of the Yellow Kid. Yellow Kids were multiplying like medieval popes.

Another significant consequence of this rivalry was that reporters, following the mandates of their editors, began to embellish the news so that stories became more interesting, more provocative, and most important, more profitable. The journalists weren't exactly lying; they were enhancing. Headlines shouted at potential readers; exclamation points marched in lines as if to war; feelings of crisis and dread uncertainty were inculcated and exploited. Critics of the new journalism called it "yellow journalism," with the "yellow" coming from—you guessed it—the nightshirt of the Yellow Kid. Facts moved from the driver's seat to the rumble seat, principles bowed to expediency, and reality morphed into rhetoric. Journalism became damned near as fictitious as the funny papers.

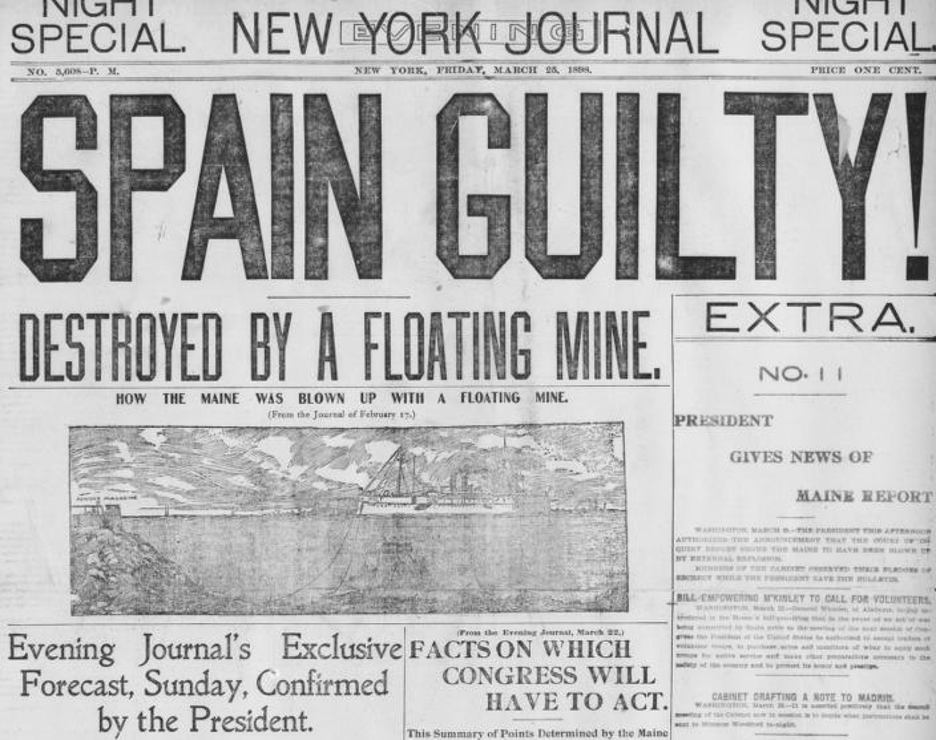

Take, for example, the explosion and sinking of the Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898. An exploding ship sells a lot of papers, but if you create a villain with imperial ambitions, say, the Spanish, you can sell a whole heap more. A first principle of yellow journalism is that you always sell more papers when the story is framed as "us" against "them." Then you dress it up in a 216 point font, call in the exclamation points, and back it up with a searing op-ed piece.

Walker, Malea. "The Spanish American War and the Yellow Press." Headlines & Heroes. Library of Congress Blogs. February 26, 2024. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2024/02/the-spanish-american-war-and-the-yellow-press/

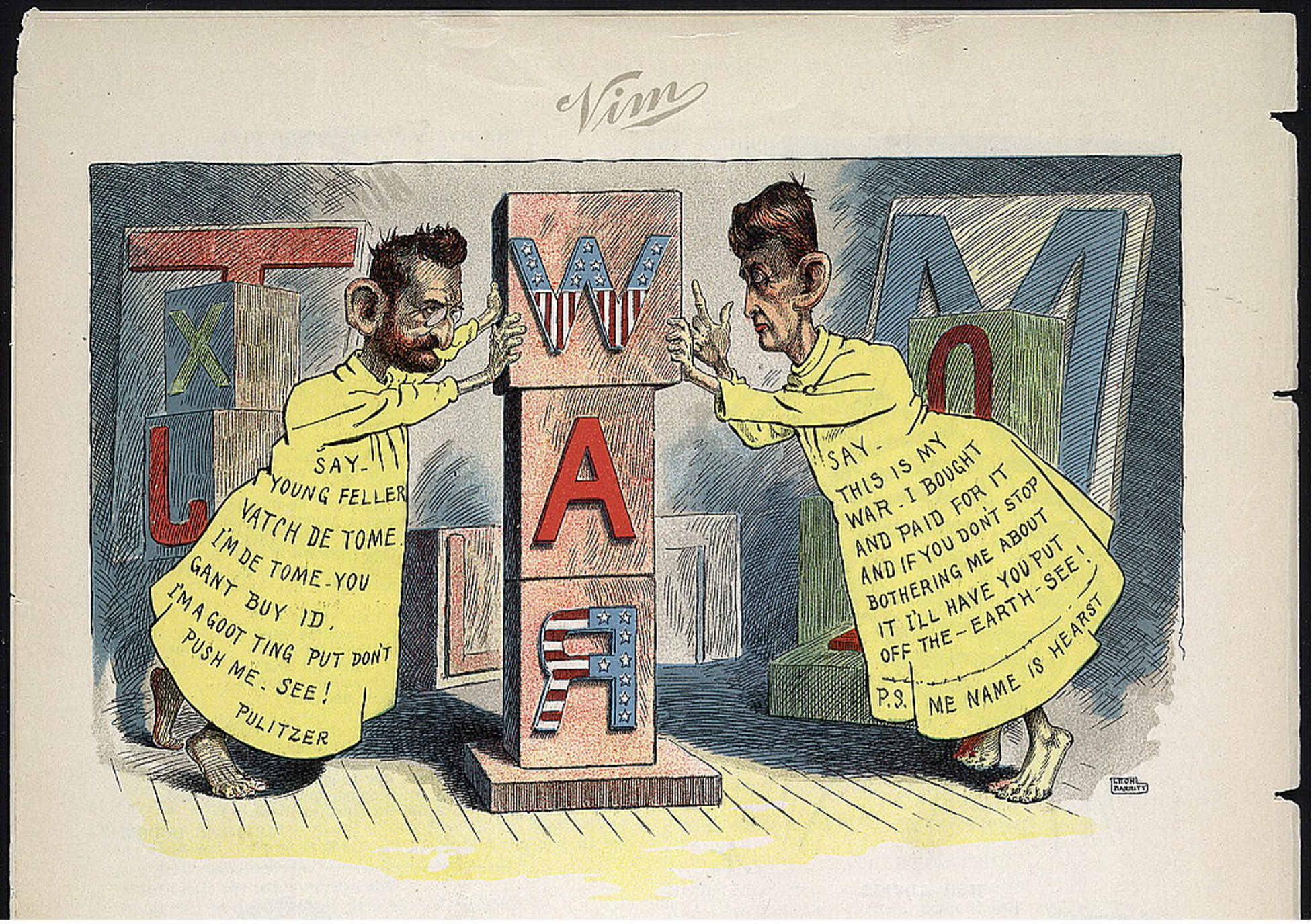

The following editorial cartoon depicts the rivals Pulitzer and Hearst dressed in yellow night shirts and trying to outdo each other with font sizes and decorative type:

"The big type war of the yellow kids," Vim, v. 1, no. 2 (29 June 1898). Prints and Photographs Division.

Walker, Malea. "The Spanish American War and the Yellow Press." Headlines & Heroes. Library of Congress Blogs. February 26, 2024. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2024/02/the-spanish-american-war-and-the-yellow-press/

As the cartoon suggests, yellow journalism also gave the governmental powers a monumental opportunity to further their own interests. Chief Intelligence Officer of the Navy, Lieutenant Raymond P. Rodgers; Secretary of State John Hay; and President Theodore Roosevelt loved yellow journalism because they wanted to go to war against the goddamn Spanish. In a great journalistic circle jerk, what was good for the sales of papers—yellow journalism—proved to be good for the government—propaganda for whatever they wanted to do next—which also proved to be good for newspaper sales, the increase of which was attractive to advertisers, which happened to be good for the funny papers, which happened to increase subscriptions and so on and so on: ka-diddle-ka-daddle-ka-diddle-ka-daddle-ka-thump, shp.

Even the technology in 1898 was perfectly suited for the rise of yellow journalism. Almost all news reports were circulated among newspapers via telegraph because the telephone was still in its infancy. In the late 1800s, most telephone exchanges were local with no more than twenty to thirty subscribers. Of course, when the telephone spread to every city and burg, the telegraph would pass into obsolescence, but that was still a ways off. And that meant the telegraph was not just the favored means of long distance communication; for most towns, it was the only means.

There were a couple problems with the telegraph, however. The first had to do with expense: The Western Union charged by the word which made sending a telegram costly. Even with the rise of the Associated Press and the discount provided to newspapers, a long story was damned expensive to telegraph. So, to save money, the first telegrapher in the queue would send out a story with a variety of codewords. The telegraphy code was complex enough, but the fact that people could be trained to read Morse Code and communicate in code words amazed Mack. In every age, geniuses arise that adopt and improve the technologies of the day.

But that didn't solve the problem entirely because stories can be complicated and code words referred largely to cliches and figures of speech. So, in order to save more money, the first telegrapher would send out stories with keywords thematically associated with one another, thereby leaving gaps between the words—lacunae is the technical term—for the recipients to fill in as they intuited. In almost every case, the interjections made the story more lurid and entertaining than the original. The "truth" became increasingly fuzzy and a lot more fun.

What was true for the big papers was also true for the smaller ones. In order to be successful, homespun jibber-jabber was not enough. Readers wanted their own Yellow Kids who blundered about in their own alleys and villages, so rural cartoonists emerged from the woods to try their hand at creating local funnies. Readers also wanted the same yellow journalistic stories of violence and tragedy and sexual miscreancy they found in the city papers, so local newspapers sought out such stories and embellished them. Speculations were reported as true, and many an innocent idiot was pilloried in the court of public opinion. In a downward spiraling circle jerk of diminishing returns, readers, all readers, wanted more and more outrageous news reports. Readers, all readers, loved hangings at the ends of nooses and sizzlings in electric chairs and the cutting of throats of ill-reputed women. As Homer observed long, long ago, "Rage is like smoke under a beehive; the bitter honey drips into the heart and tastes sweet" (Bulfinch's paraphrase). Rage and violence and sex and the Yellow Kid and the sinking of the Maine sold more papers than ever had been sold in the history of journalism.

Now back to the Neosho Rustler and young Mack McQuary. "Yellow journalism" was the only part of the newspaper business Mack McQuary really enjoyed: He loved distorting the reporting and embellishing the telling. He smirked at his yokeley neighbors' submissions, smudged and printed as if the authors had gripped a pencil in their fists and ground the lead into a piece of cardboard. Mack read their articles and thought, "Stupid idiots. Well, let's just see what I can do with this."

He took Mrs. Whittley's article about a bake sale at the Presbyterian Church and transformed it into something akin to a pastry competition on the Champs Elysee. The theft of Jeb Flander's pig was the work of a criminal mastermind. And the crowning of Miss Daisy Dilby at the Ozamo County Sweet Young Thing Contest was nothing less than an epiphany of Aphrodite herself.

As you might expect, A.L. chided Mack when he first started practicing the dubious alchemy of yellow journalism, but when the Rustler outpaced all its rivals and even drove a major competitor out of business, A.L. held his tongue. He told himself he should "give the boy a chance."

Mack had a gift well-suited to the times.