Chapter 2: Historical Notes

Documentary Evidence and Analysis

The Book Advertisement

The actual advertisement as it appeared

The Kansas City Times, Saturday, Feb. 24, 1899

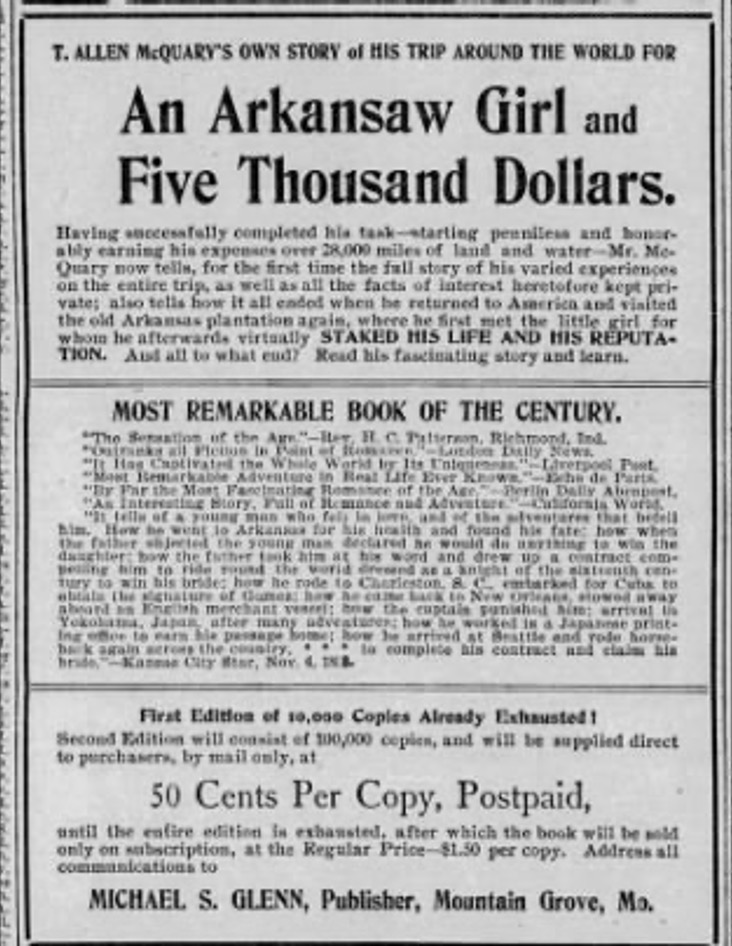

This advertisement appeared in The Kansas City Times, Saturday, February 24, 1899 and demonstrates M.S. Glenn's promotional tactics. Note the claim of "10,000 copies already sold" - no copies of this book have ever been found.

View original on newspapers.comThis remarkable advertisement from The Kansas City Times (February 24, 1899) demonstrates the sophisticated marketing campaign that McQuary and his partner Michael S. Glenn orchestrated around the Purple Knight story. The ad's breathless prose and international testimonials reveal how they transformed a regional con game into what they claimed was a global phenomenon.

Marketing Genius or Elaborate Fraud?

The advertisement lists testimonials from publications across the globe—London, Liverpool, Paris, Berlin—suggesting McQuary's story had achieved international recognition. However, many of these "testimonials" may have been fabricated, part of the elaborate fiction surrounding the entire enterprise.

The pricing structure (50 cents by mail, $1.50 on subscription) and the claim of "First Edition of 10,000 Copies Already Exhausted!" were standard marketing techniques of the era, designed to create urgency and legitimacy.

What makes this advertisement particularly fascinating is how it blurs the line between marketing and mythology. Glenn and McQuary weren't just selling a book—they were selling a legend they had created about themselves. The "Arkansaw Girl" spelling, as McQuary notes in his memoir, was a deliberate choice to give the story "homespun credibility."

The Publishing Partnership

Michael S. Glenn's role as both publisher and co-conspirator reveals the collaborative nature of the McQuary deception. Glenn provided the literary legitimacy and business acumen while McQuary supplied the charisma and performance skills necessary for the lecture circuit.

Their partnership represents an early example of what we might now call "viral marketing"—creating a compelling narrative that spreads through media coverage and word-of-mouth, generating its own momentum and commercial opportunities.

The McQuary Family

Vertrude McQuary mentioned in local social news

Vertrude was T. Allen McQuary's sister. While her brother spun tales of circumnavigating the globe, she remained in Missouri, appearing in local social columns.

During his decades in Galena, McQuary lived an outwardly respectable life with his second wife, Naomi. The couple were fixtures at local teas, bridge clubs, and social gatherings - a far cry from his claimed adventures as the Purple Knight. Naomi stood by him through these quiet years, unaware perhaps of the darkness that would eventually surface in postal embezzlement and suicide.

Adding to the irony, McQuary's father was a minister in the Christian Church and owned a resort on the James River. The son of a preacher, married to a faithful wife, teaching Sunday School - yet harboring the same deceptive nature that had driven the 1897 hoax. The respectable facade held for decades before finally cracking in 1948.

The Price of Respectability

McQuary's memoir reveals the tedium he felt in his respectable life - following Naomi to "luncheons and bridge clubs" like "a faithful dog, a beagle, say, or a Pomeranian." This domestic tranquility was built on the foundation of his earlier deceptions, and ultimately could not contain his fundamental dishonesty.

The newspaper clipping showing Vertrude at a Ladies Aid meeting represents the kind of mundane social obligation that McQuary found so stifling, yet participated in as part of his decades-long performance of respectability.