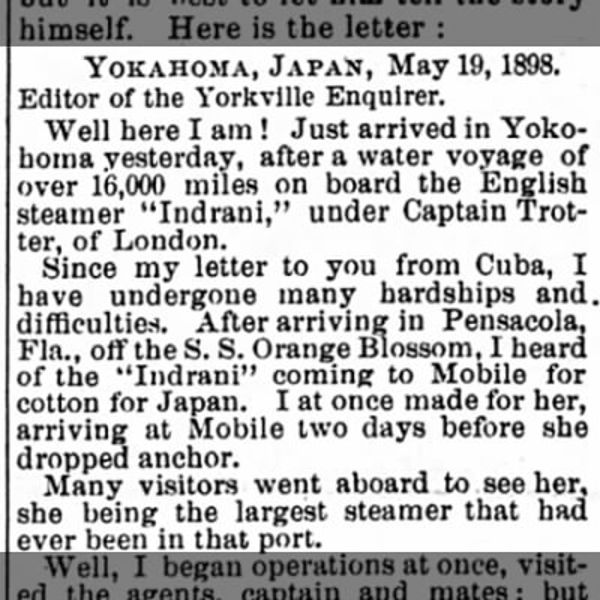

Chapter Nineteen: Mardi Gras in New Orleans

February 22, 1898

In the end, the Orange Blossom was prevented from entering the port in Havana because an explosion on the USS Maine killed over 260 American sailors and sent the ship to the bottom of the harbor. The papers immediately blamed Spain, and the cry, "Remember the Maine and to Hell with Spain!" was on every patriot's lips. This in spite of the fact that no one really knew who or what sank the Maine. It could have been the ship's own boilers or an ammunition magazine that exploded. Perhaps another country was responsible or an anarcho-syndicalist fanatic from Russia. Who knows? But never forget those enticing gaps in telegraphed messages just waiting to be stuffed by warmongers in the State Department, important men who had no qualms about bribing reporters who had no qualms about taking government money and who were employed by publishers who had no qualms about taking government money and so colluded with the important men to stuff the lacunae with warmongering propaganda.

"Fire when ready, Hearst!"

"Man the howitzers, Pulitzer!"

War was in the air, and the captain of the Orange Blossom deemed it too dangerous for the ship to harbor in Havana. The sloop made a loop around the Florida Keys and sailed back to the mainland. So much for Cuba, and McQuary's tete-a-tete with Gomez.

The temperatures in the Gulf were balmy compared to the Atlantic, and the Orange Blossom anchored at Pensacola under the benign gaze of a mild mid-winter sun. Mack went ashore on a dinghy rowed by two black Haitians and learned from a couple sailors at the Tidewater Tavern that a steamer, the Indrani, had just departed Pensacola for Mobile, Alabama, where she would take on bales of cotton to sell in Japan.

Japan! Mack thought. I must be on that boat!

So, Mack bought a train ticket for Mobile and was waiting on the wharf for the Indrani when she entered the bay. He boarded the steamer, introduced himself to the captain, one Theophilus Trotter by name, and begged him for employment as a deckhand. Mack declared, "I'll shovel coal to stoke the burners or swab the deck or dump the slops, anything to sail with you!"

But Captain Theophilus Trotter hated Americans and particularly American sailors, and he turned Mack down flat: "I'll burn in hell before I hire a Yank!" Or something to that effect.

In desperation, Mack persuaded a Dutch sailor to smuggle his duffle bag aboard the boat—he had traded his saddle bags for a duffle bag when he sold Roz at the docks in Charleston—and then went to the station and bought a ticket for New Orleans, which, he learned, was the Indrani's next port of call.

At precisely 2:35 PM, Mack boarded the Piedmont Express in Mobile and arrived in New Orleans two days later, on the eve of Mardi Gras. The passengers on the train had been giddy about Mardi Gras, and one fellow even wore a red cape and zucchetto. Mack had never heard of Mardi Gras before, and he thought they were talking about a fellow named "Marty Graw."

Such an innocent, unschooled boy.

Mack found pleasant lodgings on the Rue Dauphine, donned his uniform, and went to a place called Antoine's for dinner, though he had never heard of that famed establishment. The waiter admired his purple attire, or so Mack gathered, because he said the chef was experimenting with a dish called "Oysters Rockefeller" and "a fine looking young fella like yourself might cotton to it. Courtesy of the house."

Every person who has ever lived has experienced a numinous moment in which he imagines he might become a Carnegie magnate or she imagines she might become an Astor heiress, and in that transcendent moment, that person truly believes he or she will never die. For Mack, that moment occurred at Antoine's with the first bite of Oyster's Rockefeller. Until then, food had not stirred any intimations of immortality. But New Orleans does that: She exploits every sense to lure us on with an insatiable desire for immortality and immorality, immotility and immodesty. Ah, New Orleans, how we yearn for the warm embrace of your octaroons and the sea-salty taste of oysters and the genial Catholicism that presides with a smile and promises expiation!

After dinner, Mack loosened the belt of his purple breeches and made his way to the famed and infamous Bourbon Street. He was both delighted and dismayed to see people in the most outlandish costumes: men were women, women men, many people were animals, and a chimpanzee in a tuxedo sat on the curb, smoking a cigar and baring his teeth at the girls. Mack was delighted because all differences had melted away in the grand melee of Mardi Gras but also dismayed because the purple attire that distinguished him in mid-America was downright mundane in New Orleans.

A purple knight walking down Bourbon Street is just another man.

Nevertheless, Mack had two adventures worth recounting, though he never spoke of them back in Galena, Missouri.

The First Adventure

A group of partiers invited Mack to join them at the Old Absinthe where he imbibed strange spirits and chatted with fairies and clowns and pretty girls in feathers. At least he thought they were girls; he wasn't sure. It was Mardi Gras, and everything was topsy-turvy. One of the girls who was decked in green said to Mack, "I'm going to make you something you'll like." She set a small, green glass embossed with grape vines on the table and laid a slotted spoon over the glass. She smiled at Mack and said, "Now for some sugar, sugar. You are my sugar, aren't you?" Mack said, "Well, I'm sweet on you, so I guess I am." With a dainty pair of tongs, she set a sugar cube on the slots. "Now a little ice water to sweeten the bitters." She began pouring water from a green pitcher over the cube. When the cube dissolved, she handed the glass to Mack. "Bottoms up, sugar." Mack sipped the drink while the green girl watched, and as he drank, the Purple Knight and the Green Girl were becoming more real to each other, more palpable; their gazes were deeper and their prospects more exciting. Finally, Mack tipped up the glass and swallowed the remaining slurry of sugar, and when he lowered the glass, he found the girl watching him with a very interesting expression.

Mack was falling ever more deeply in love with New Orleans.

Suddenly, an uproar of shouts and "huzzahs"! The revelers began chanting "Storyville, Storyville, Storyville," and though Mack knew nothing of Storyville, he chanted with the rest, and the Green Girl started laughing and chanting, too, and the fairies, clowns, and feathered girls spilled from the bar and roistered up the street. Mack was happy because he loved a good story, his stock and trade was telling stories—indeed, he was a story!—so Storyville sounded like fun, like a good story well-told. Everything in New Orleans was fun, especially the Green Girl with her come-hither tongue.

As they stumbled from the Old Absinthe, Mack asked her, "What's the story of Storyville?"

"How to describe Storyville?" mused the Green Girl. "Storyville is a very special part of town. They call it the 'red-light district,' which makes no sense because red means 'stop,' and Storyville is all going forward into what you want to do. And the most special place in Storyville is Mahogany Hall."

"What's so special about Mahogany Hall?"

"You'll see, Purple Boy." Then she kissed Mack hard and pulled him into a narrow alley where he enjoyed an intensely pleasurable moment before he and the Green Girl hurried to catch their group, who had just turned the corner to Basin Street.

Mack had assumed, reasonably enough, that Mahogany Hall was named for the wood, but he was wrong and happily wrong at that. Mahogany Hall was actually a plain edifice of pale bricks, paneled inside with mirrors and supplied with hot baths in every room. "Mahogany" referred to the luscious brown girls who lived and worked there. For the rest of his life, Mack would recall the brown girls, languid and compliant in a pleasant fog of absinthe and steam, girls with green eyes—chatoyant—girls supple and soft to the touch, girls naked beneath sheer gowns of organza.

A coppery girl came to Mack and put a wooden cup to his lips, and he drank while she whispered to him in French. She cooed like a mother soothing her child, and as he drank, the girl became softer in the candlelight, more alluring, more enticing and oddly maternal at the same time—and he felt as if he was merging into her warmth and her scents of lilac and cardamom and petrichor, as if she were wrapping him in spiced cotton sheets to entomb and resurrect him. The tall mirrors melted into lozenges of mercury so that images and bodies ran together, and Mack, too, dissolved like a sugar cube on a slotted spoon, down, down into warmth and desire. From far away, he heard laughter, and Mack turned to see his new friends standing around the Green Girl and a Mahogany Girl, and the girls were kissing and petting one another and the organza shift fell to the floor, and the Green Girl moaned and pulled the Mahogany Girl close and kissed her again. Mack began laughing and thought, How delightful that pretty girls should caress one another in the marble parlor and mirrored walls of Mahogany Hall! He laughed at Oysters Rockefeller and the scent of petrichor and the fawn-soft girls. Yes, Mack loved all girls who loved pleasure, who loved to give and receive pleasure, whose motive in being was pleasure. Bare arms reached around him from behind and began unbuttoning his doublet. A tongue flicked along his ear lobe, and Mack leaned back into the warmth of murmured words and expert caresses. Soon, two mahogany girls were leading him up the stairs. The stairwell was redolent of perfume and steam and funk.

The next morning Mack awoke alone and rested. His purple costume was folded neatly on a chair, and on top of it lay the sword and poinard crossed like an X. His mask dangled from one post of the brass bed, and his plumed chapeau adorned the other. The room smelled of lemon and anise, but from downstairs came the odor of strong coffee. He put on his clothes and checked his wallet. Empty.

Fair enough, he thought. I can't remember how much money I had, but irregardless, the night was worth it.

His memory was a confused swelter of beige and mahogany bodies and steam and pleasure. He was happy. Mack took the mask from the bedpost and tied the strings behind his head and looked in the mirror. He had a beard coming on, but then he recalled he was in New Orleans, and a purple mask and stubble made no difference to anyone in New Orleans. Then he remembered, Today is Mardi Gras!

Then on the heels of that realization, a subsequent thought, The Indrani! That's why I'm here!

Mack put on the rest of his costume, belted on the sword and poinard, inspected himself in the mirror, and satisfied that he was satisfactory, hurried down the stairs for breakfast. In the parlor, a long table was set with urns of coffee and a platter of cold beignets and a small wheel of cheese. The mirrors had become empty windows into the lamplit parlor. In the corner, a talcum-powdered plumpish lady sat comfy in a cushioned chair; she was knitting a pink shawl. From her shoulders and age-wrinkled decolletage flowed a pink dressing gown that conformed to her various mounds and hillocks. From the scalloped sleeves of the gown protruded pale, dumpling hands, and from the scalloped hem, plump ankles in pink stockings with little feet encased in pink slippers. Her riven cheeks were powdered with pinkish rouge, and her lips were as pink as pale roses. The whites of her eyes were rimmed with pink. She appeared to Mack as a species of debauched grandmother, and when he entered, she looked up and smiled. "Ah, monsieur. Avez-vous bien dormi? That is, in Anglais, did you sleep good? I hope so. Now mangez! A man must feed his virilite." She spoke as if the Mahogany Hall were a place for gentleman boarders who only wanted a hot bath and a soft bed before rising early and getting back to work.

"Yes, ma'am, I slept just fine. Very comfortably, thank you." He took a beignet from the platter and nibbled at the corner. The grease left an oily sheen in his mouth, but the powdered sugar tasted good.

"Je t'en prie." She licked her lips, but quickly, like the flicking tongue of a lizard. "The people in town call me Lulu—which has not always been done—and I began the Mahogany just one year ago. One year, and in that time, I have very many happy boys and girls, too?" She laid down the needles and half-knitted shawl in her lap.

"I congratulate you on your success. May I kiss your hand?"

"Oui. That would be a nice place for you to begin, but I know a nicer place for you to finir." She leered and held out her veined and powdered hand. Mack raised it to his lips and kissed it.

"May God's blessings ever rest upon this establishment," he said.

"Les benedictions de Dieu are my entreprise, monsieur." And she spread her legs just a bit, so the skeins of yarn slumped into the trough of her gown while the needles pointed upward at nothing.

"Madame—"

"No, monsieur! You ought to say mademoiselle!"

"Pardonne et moi. Mademoiselle. Could you tell me where the parade route begins?"

"Oui. Au coin de Rues Girod et Tchoupitoulas."

Mack supposed she meant the corner of Girod and Tchoupitoulas streets, but he asked her anyway to be certain.

"Oui," she said, but under her breath, "Le beauf. Mais il est tellement mignon." [Translation: "He's an idiot but he sure is cute."] "But the parade will pass dans ma rue. Before theese very door. Monsieur could entertain me in the meantime, and then after we could watch the parade, you and me, from here. J'adore lecher!"

"Lecher?"

She licked her lips and spread her knees, and to his distress, Mack discerned she wore no culotte.

"Bon Dieu, no! I mean, I have very important business to attend to. It's a long story, but suffice it to say I must find a ship, the Indrani by name, bound for Japan, and she sails within the week."

With that, Mack bounded out of the parlor and into the street, where he stood for a moment, blinking in the winter sun. From inside he heard a voice calling after him, "Monsieur! Attendez! Monsieur? Merde!"

The Second Adventure

As if the gates of a dam had been opened, men and women attired in brown, gray, and charcoal (with occasional characters in bright buffoonery) came streaming down Basin Street, some holding the hands of children and some holding the hands of one another. Mack merged with the throng among whom he bobbed along like a purple cork. The stream sluiced down Basin and banked around the corner onto Bienville whence it flowed into the French Quarter, and Mack tossed about with it to the Rue Dauphine, whereupon he diverged from the crowd and walked in haste toward Canal. Upon turning the corner, he saw the Mississippi River gleaming dully beyond the wharves.

Ah, ha! he thought.

He was hurrying toward the river and passing Tchoupitoulas Street when a curiously attired man sitting in a window casement of a building hollered to him. "Hey, you! McQuack! It's about time you got here! Where you been? Get your ass down there! They need you, goddammit!" and he pointed to a garish assemblage of men and women and mules and floats arrayed down Tchoupitoulas. Mack forgot his intentions with regard to the Indrani, for the little man was costumed in a floral blouse and yellow stockings, and he spoke with acerbic urgency, and he was reading a newspaper in a window casement—which seemed unlikely and uncomfortable—but he felt as if he had seen this man before, in another crowd, perhaps, but fleetingly, in passing, but that man had been dressed in stolid, Midwestern attire, and the encounter had been as swift and meaningless as the swoop and arc of a swallow at dusk.

Mack hesitated, and the harlequin puckered his mouth into a pink asterisk of disapproval. He yelled, "Go on! Git!"

"But I—"

"No buts!"

Mack called back, "Do I know you?"

"The question should be, 'Do I know you?' Go!"

So Mack obeyed and turned down Tchoupitoulas Street where he joined a happy kaleidoscope of bright costumes and painted faces and wild activity, albeit wild in a strangely detached and leisurely manner, if such can be imagined. Mule-yoked floats were lined up end to end down the cobblestone street, and crews of men and women were daubing wooden frames with gold paint and pushing bunches of flowers into panels of mesh wire, and some were calming mules with carrots and lullabies. A smoky cloud with a pungent, skunk-like smell hung over the hubbub and lent a dreamlike quality to the yoking, gilding, decorating, and singing. The smoke was thick, rather like too much incense in a stone chapel. Mack inhaled the smoke through his nostrils, and the scene became a dream.

"So, you made it!" cried a voice in the street, and the floral fellow in the window was standing in the street with his hands on his hips and tapping his foot. The crowd was milling about him in its lackadaisical frenzy, and the mules stood stoically with their ears back and muzzles forward. People looked down from wrought-iron balconies and made jokes. The man, however, seemed to notice naught but Mack.

Mack said, "Who are you? I almost feel I should know you."

The Harlequin guffawed. "And so you should, you fraud! My card," and the man presented Mack with this:

A tall wo/man in a lavender gown and sucking on a peppermint stick jostled toward them through the crowd. McQuary inhaled again and said, "I've seen you, too. But you didn't look like this. Not at all. You've changed."

Candy undergoes a transformation

The wo/man drawled, "You ever been to N'arleans before . . . Sugar?"

"No, ma'am, sir . . ."

"Then you're dreamin', Sugar. I never been any place else. Ain't no other place on God's good earth for the likes of me."

Otis Bulfinch said, "Ah, this fraud thinks he's seen everybody before, Candy. He's a dreamer."

Though it was not yet noon, Candy's cheeks were peppered with whiskers, and she smelled of mint. The wo/man put the peppermint stick in the corner of his-becoming-her mouth as if it was a cigar and said, "New Orleans has got enough dreamers already. Ain't that right, Otis?"

Otis scoffed, "Yeah. Too damn many dreamers in a town that needs more reality. Cold, hard facts. Facts you can kick your foot against, Candy, like these cobblestones. C'mon, let's go."

Arm in arm, Otis and Candy disappeared into the crowd, and Mack felt himself lost in an unreality of plumes and masks, sequins and satins. Puffs of purplish, grayish smoke billowed upward from the crowd and twisted in hazy, curling columns, and the columns supported a temple of long dead gods, chimerae, heroes, and other dreams.

No, that's just a float. A float of gods. Ha. It's just a float.

Mack breathed deeply.

Should I know those two?

He looked at the card.

Otis Bulfinch. I feel like I've heard that name.

A massive bull, staid and stalwart, stood on a straw-strewn wagon bed, fenced in by rails and surrounded by fluffy clumps of cotton; he was Jove among the clouds, impassively pursuing Europa. A gold and green blanket had been thrown over his back on which the words "Le Boeuf Gras" were embroidered. The bull munched corn from a washtub while handlers appareled like the twelve apostles stood around his pen and chanted hymns to Pan.

The following float was adorned with enormous pineapples and palm trees, and men dressed like pineapples waved palm branches and thin wands, while from the bed of the wagon sprung magnificent fern leaves of white and gold.

Behind the Pineapple Float was the Rape of Leda Float. Zeus in the form of a magnificent gold and white Swan was bearing away poor Leda, a dark haired, somewhat Brobdingnagian girl in a Grecian gown: poor not only because she was raptured away against her will, of course, but also because of the patriarchal inversion that denied Leda her cygneous significance and sinuous sensuousness and transferred her swanlike qualities to the dour, unsmiling, not to mention heavily muscled, god of the skies and diminished her to a supine prize hanging limply from the beak. The notion that Zeus could become a swan is laughable, ridiculous, and completely unworthy of swans.

Mack thought, Swans are like girls, and girls are like swans. Everybody knows that.

Someone handed Mack a small clay pipe with the words "Smoke me" stenciled on the bowl. He did, and the giantess presided over the melee like St. Bridget of the Highlands, nursemaid of Jesus, and nurturer of barley.

Next was an Oriental affair umbrated by a massive parasol with a small pagoda as an afterthought and peopled with kindly shamans who wore shallow, bowl-shaped hats and blessed the crowd with incongruous thyrsi.

Mack coughed a small, bitter cloud of smoke and turned away from the bowing Chinamen, for following the pagoda was a Greek temple replete with enormous amphorae and two snow-white, winged Pegasi and a terraced Mount Athos that rose higher and higher and concluded with an empty throne labeled "King Comus." and Mack thought, That's what I'm talking about.

For this, this was a throne worthy of the King of Carnival, a throne worthy of the Purple Knight of Missouri, a mount worthy of T. Allen McQuary!

It is a little known fact, indeed, completely unknown until this very moment, that none other than Mack was the King of the Krewes, the Grand Marshall, the Lord Comus! The first movie ever filmed in New Orleans just happened to be the Mardi Gras Carnival of 1898—it's true—and if you watch it, you will see Mack perched high on the throne. The beard, of course, was plastered to his face, and the purple costume hidden by the cloak. But it's Mack up there waving and gesticulating from the high throne. Swear to God. You can watch it here:

Here's how it happened.

As I say, revelers were scurrying around the floats, daubing paint and arranging flowers and making last minute adjustments to their costumes: buckling belts and tying masks, stuffing pantaloons into boots and smoothing makeup on their cheeks. The drivers had climbed onto the wagon benches and were brandishing braided whips, and even the mules sensed the excitement: Their ears perked upright, and they nodded their heads and snorted.

It was at that moment, that very moment, a man sprinted around the corner from Lafayette, waving his arms in dreamy panic, rather like the tentacles of an anemone, and calling out, "Rex? Rex? Dammit it to hell, where is Rex?" The frantic man wore a long Chinese gown with random Hanzi characters embroidered down the seams; his eyes had been orientalized by make-up, and a long forked beard was glued to his chin. He began turning men about to look at them, and he yelled in their faces, "Rex?" The men said to him, "Whoa up, Sinclair! Whoa!"

"What's done crawled up your ass?"

"Take it easy. And suck you some Sen-Sen. Yo' breath smell like buzzard shit."

"Goddammit, boys, this ain't no time for the laissez faire! Has anybody seen Walter? Where the hell is Walter?"

Candy said, "Hold steady there, Si. This morning early, I banged on Walter's door, and Mizz Walter, she say, Walter ain't here. He most likely with his lady friend." Candy was becoming more herself in a profound transmogrification.

Candy becomes ever more herself

"Whaat? And Mizz Walter, she's okay with that?" asked Otis. He was aghast.

Candy said, "Who knows? Mebbe she don't pleasure him no more, so he gotta squirt his juice somewheres else. No fault of the man if that's what it is. Ain't mine to cast stones."

Candy's ethical (and biological) assessment of Walter's philandering started a heated discussion on the many justifications for adultery, when Otis interrupted with another pertinent question, "Well, did you ask Mizz Walter who his 'lady friend' is?"

"'Course, I did," said Candy. "She say, 'He with the Countess, who else gonna fuck a old goat like Walter?'" The men nodded in agreement at Mrs. Walter's surmise. The Countess had pleasured them all at one time or another, and her penchant for older men with money as well as her sexual creativity was renowned. Furthermore, she seemed impervious to disease, and no man who enjoyed her ministrations ever complained of pediculosis pubis.

"Well, didjoo ask the Countess where Walter is?" asked Sinclair the Ersatz Chinaman.

"Whatchou think? But she say she ain't seen him neither." Candy shrugged her shoulders as if to say, "I dunno."

And then, suddenly (but not suddenly as in a startling interruption, but suddenly because peremptory, thereby marking an alteration of thought, a return to the matter at hand, and a motive to motion), into this lull of perplexity resounded the sonorous bells of St. Louis Cathedral; the heavy "bongs" echoed broadly over the city and along the streets and merged into the skunky haze that hovered over Tchoupitoulas Street, whereupon the smoke and knells mingled together to wreathe around wrought iron railings and sift through casements into apartments.

Bong. Bong. Bong.

Even more ominous than the leaden bongs were the dark clouds rolling in from the Gulf. The southwest sky was all charcoal, and gulls wheeled bright white against the gray-black canopy.

The men looked about as if they could see the notes of the tolling bells and held out their hands as if the rain had already commenced, and for a moment, Walter Florius, King of Kings, Mayor of New Orleans, businessman, and frequenter of whorehouses, was forgotten. But not by Sinclair the Ersatz Chinaman, who began yelling again, but with wilder urgency, "You buncha dumb bastards! We gotta start the parade! People are waitin' up and down the streets and soon they gonna get mad! Where's that goddamn Walter?" This time, pandemonium seized the men and precipitated a feckless, bumbling search in which they rotated in tight circles and jostled each other and shrugged their shoulders.

At that moment, that very moment, a strange looking boy, a prodigious child as bald as a gourd, came floating over the chimney tops and down Tchoupitoulas Street to light gently on the high throne of Comus. His yellow nightshirt fell to his ankles, and his smile was fixed and unnerving. Mack was the first to see him, and he shouted to the people in the street, "Look! Up there! On the tower!"

And the people in the street said one to another, "That man in the purple clothes done lost his mind. He sees somethin' in the sky ain't there to see."

But Otis and Candy approached Mack on either side and seized his arms. "Let's go, McQuack! We've got you now!" said Candy.

"Yeah," said Otis Bulfinch. "You are your own worst enemy! Ha!"

Mack asked, "Where are you taking me?"

And Candy gruffed, "Where do you think? Up there . . . to your throne!" And together, they half-carried, half-dragged Mack to the Grecian Comus float.

The Yellow Kid waved at Mack from atop the high tower and chortled. "Hell-o-oh, McQuacky! How you like my new wings? I bought 'em special for this occasion." He turned around to show off his orange and black butterfly wings. "I'm a monarch flutterby"—he flittered upward and touched down again—"the Butterfly King, Silly Psyche, Comic Comus, at your disposable." And the Yellow Kid bowed so that Mack could see the top of his globular head and the two antennae that quivered behind his shoulders.

At this, Mack thrust Otis and Candy so that they stumbled away from him, and they withdrew, giggling, into the crowd; then, Mack seized the edge of the float, hoisted himself on the deck, adjusted his mask, and spake aloud to the crowd: "Enough of this!"

And the people said to Mack, "Enougha what?" while to one another they whispered, "That purple boy done absatootley lost his mind."

With stentorian dignity and his hands held high and his feet set apart, Mack proclaimed, "My name is T. Allen McQuary known to the world as the Purple Knight of the Ozarks. I have been featured in the most respectable papers of the Midwest and the South, and, yes, the New York Times, and even now I seek the vessel Indrani so that I might continue my quest around the world for a girl who is lovelier than a butterfly and sweeter than a powdered beignet! Her father promised me her hand if only I can circumnavigate—"

On and on, Mack recited the story, and the people grew still as if enchanted, and he regaled them with lies and stories, and in the telling, he became more and more real, both to himself and to the crowd. Meanwhile, the Yellow Kid was sing-songing from above, "Oooh, I like beignets! Hully-gee, I do! A girl as sweet as a doughnut would be yummy in my tummy! I can see my Mummy and Poppy from up here! Hello, Mummy! Hello, Poppy!"

Otis and Candy waved at the Yellow Kid, and the Yellow Kid blew kisses to them.

The people in the street decided Mack was not crazy, not at all; they thought he was putting on a show in the "true spirit" of Mardi Gras.

"Ha-ha!" they laughed.

The people were watching and listening, spellbound by Mack's strange peroration and spasmodic gesticulations and the whole weird turn of events—Walter Florius gone missing and the Purple Knight of the Ozarks gone mad but speaking to them now of Love from the bed of the Mystick Krewe of Comus.

Mack had arrived in Storyville!

But in the street, Sinclair the Ersatz Chinaman was stroking his stringy beard and thinking.

"Ah, ha!" said he.

So it was that Si climbed onto the bed of the Mystick Krewe behind Mack and tiptoed his way to Mack's shoulder. One finger he laid over his lips but with the other hand he gestured to the crowd and said, "Excuse me, Mr. Purple Knight from Missouri, for interrupting, but I have an idea!" Then Si shouted to the heavens, "Ecce homo: This fella ain't lyin'! There was a story about him in the Picayune last week! He's a regular Don Quixote, this guy!"

A woman said, "Yeah, I read that article; it went just like he say. He's the real deal!"

The crowd responded with "yesses" and "you bets" and "hoorays."

Si raised his hands again and said, "'Zactly! If you got ears, let 'em hear! Walter Florius is nowhere—nowhere!—and the bells of St. Louie are bonging, and we need a king. And now this young fella shows up in a purple outfit as if he dropped outta Heaven, and he's crazy as a mud turtle but a good lookin' young man all the same! Let us crown him Comus, King of the Mystick Krewe!"

Mack burst forth and brandished his sword as if the crowd had not already been convinced and cried out, "I bear the sacred Sword of the Knights of Pythias!"

Far above, the Yellow Kid fluttered upward, clapped his small hands, and said, "Oooh!"

Sinclair the Ersatz Chinaman spoke again to the crowd, "Y'all like that sword, doncha?"

More acclamations and an old woman hollered, "You bet your ass we do!"

Otis and Candy began chanting, "Crown him King! Crown him King!" while they looked sidelong at one another with sardonic smiles and ironic eyes. The crowd took up the cry, and a happy clamor rose above Tchoupitoulas Street to mingle with the haze and echoing bells.

"So be it!" Sinclair the Ersatz Chinaman placed his hands on Mack's shoulders, and said, "I anoint thee Rex Regum, Mystick King of the Krewe of Comus, the Master of Mardi Gras, and High Slave of Venus!"

Mack wasted no time in replying, "I have ever served Venus with a true heart and a rigid scepter! With all humility, I accept! Crown me Rex, and I will lead your people!"

The Yellow Kid started clapping, and he hollered, "Yay, and hully-gee!" And opening his wings, he fluttered upward and away from the now vacated seat of Comus and over the chimney tops of New Orleans to the Mississippi River, Father of Waters, that gleamed dully as it writhed past wharves and docks to spill muddily into the Gulf of Mexico where men in boats lowered nets to haul up red snapper and grouper, amber jack and shrimp.

With careful solemnity, Sinclair the Ersatz Chinaman draped Mack in an ermine-collared cape of green and gold, crowned him with a golden coronet inset with emeralds, and invested him with a golden scepter topped by an emerald orb. A blotto bishop in powder blue vestments and a pink mitre raised his hands in blessing. Everyone knelt, and Mack was turning to climb the many-tiered tower when Sinclair yelled, "Hold a minute! He got no beard! He's gotta have a beard!" A boy with a girlish face, sinewy in motion and wearing a gold and green kimono, slithered toward Mack: The boy bore a silver tray on which lay a beard and a little pot of paste. The Blue Bishop made the sign of the cross (in reverse) over the silver tray and its elements, and Sinclair smeared Mack's face with paste and affixed the beard.

"That's better," said Sinclair. "Now up with you!"

Mack ascended the tower while the incensed smoke rose around him, and the people hollered hallelujahs in the street.

Having mounted the high throne and looking on the crowd below, Mack felt more fully alive than he ever had before, even more alive than when the sisters Patricia and Allie pleasured him in the annex of the First Presbyterian Church of Richmond or when he marshalled the Charleston parade and was chosen afterward by the Odd Fellows as their Man of the Year, yes, even more alive than when the mahogany girls expert in love drained him utterly and left him to dream on a strange Carpathian hillside. All the girls who gave themselves to him seemed insignificant to him now, and he realized with joy, This is what I always wanted! And as he inhabited the sacred sphere of unwarranted achievement, he remembered the deceived fathers and clucking mothers and sullen brothers suspicious of his intentions, and they disappeared like smoke in the breeze of a coming storm. Mack felt as though he were floating, as if he were watching himself from a great distance through a telescope: a golden-green king resplendent forever.

Then Sinclair yelled to a Beefeater in red and green livery, "What the hell you waitin' for, Benny? Let's go!" The Beefeater blew a clarion note on a trumpet, the mules snorted and pulled, and the Bull swayed briefly when the wagon lurched into motion. One by one, the other floats followed, rattling over the cobblestones, and the temples and towers and swans wobbled and quivered. An abrupt jerk caused Mack's crown to slip forward over his eyes, but he quickly put it back in place, and when the King of Comus turned onto Canal Street, the people shouted, "Yea!"

The Mardi Gras parade had begun.

Standing alone on Tchoupitoulas Street, Otis and Candy waved at the departing parade, and Otis said, "Well, there he goes—"

And Candy completed the thought, "—his own worst enemy."

As Mademoiselle Lulu foretold, the parade did indeed pass before her door, and from his high throne, Mack waved to her as she sat in the doorway in a rose-pink bergere chair. Alas, she did not see Mack because she was appraising the soldiers who marched street-level before her. She blinked away the tears from her red-rimmed eyes, and she licked her pink striated lips.

Alas and alack, let us bewail the misery of memory!

Mack watched Lulu watching the soldiers and surmised she was recalling dalliances with young men long dead. In a second story window above Mademoiselle Lulu, the mahogany girls lounged before the open windows—slim, tan, and languid, their bodies naked beneath sheer organza. Mack saluted the girls, too, and they blew sleepy kisses in his direction. One of the girls touched her finger to her tongue and let it enter her mouth.

The parade wound through the cobblestone streets where crowds in somber worsted clapped, and children ran for candy thrown by careless clowns. And all the while, clouds crept in from the west to block the sun, and the day grew chill. A few heavy drops fell and splatted on fedoras and parasols and the tottering floats, but the parade meandered on, a procession of festoons and buffoons and faux golden doubloons, all bright and merry beneath the charcoal sky. And there, up on his throne and gleaming between the dirty cobblestones below and glowering clouds above, like a sprig of mistletoe on a barren oak or the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, shone Mack the Illustrious, the Lord of Misrule, Debaucher of Girls, Teller of Stories, and Rex Nihili, smiling and waving and bowing in mock humility.

When the parade ended at the corner of Napoleon and Claiborne, Mack clambered down from his perch and chattered to anyone in proximity about the success of his performance and how much the people loved him and, of course, how much he loved New Orleans, and when the proximate people ignored him, he changed tack and intoned with stentorian dignity, "Thank you all for having me as your king. I am deeply humbled." And so forth.

The people in various stages of dishabille grunted "fuck you" and "piss off" and other unpleasantries. The fact was, the carnival was over; whatever fickle impulse had inspired the people to elevate Mack had passed; Lent was already laying its cold limp hand upon their hearts. Back into closets went costumes that would yellow and stiffen and be eaten by moths; out from drawers came prayer books and beads and scratchy scapulars.

Sinclair the Ersatz Chinaman came to Mack and said, "Hold still." He began removing Mack's beard in a tedious process that involved peeling it back a quarter inch, softening the glue with turpentine, sponging off the glue and turpentine with soap and hot water, then more peeling, more turpentine, and so on until he finally tore the beard away with a short ripping sound. Otis was on hand to give Mack a mirror, and his face was as ruddy and chafed as if it had been burned by the summer sun.

"So was it worth it?" asked Otis.

"Yep," Mack said.

Candy had returned to manhood, and he shook Mack's hand with a firm grip. "Good work, pal. Fine job."

The heavens split with a crack, the rain fell in gusting waves, and Mack was drenched once more with purple dye.