Chapter Fifteen: Otis Bulfinch Has a Dream

One good cartoon deserves another

February 20, 1898

Sullen August had long ago died into subtle September, who passed the scepter to crisp October, who touched the trees with her magic wand, so they began dying in shades of orange. November soaked the russet leaves and tugged them from the twigs when white December cloaked the hills and the clean air smelled of woodsmoke. Then came brittle January, bright and icy with a glaze around the ponds followed by frigid February with her forlorn trees and hopeless valleys, an abbreviated month that nevertheless seems as if she'll never stop groaning and whistling, and that's where we pause. For Otis Bulfinch was stuck in his office on a cold February afternoon: forlorn and huddled by a radiator that groaned and whined and seeped rusty water.

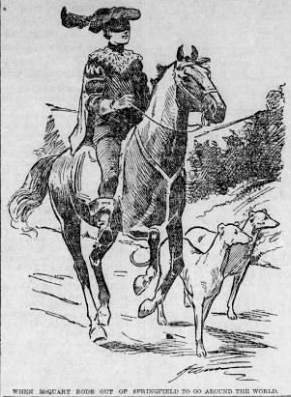

In the declining years of the 19th century, most folks still marked the passage of time according to the rhythms of nature. "Most folks" but not Otis Bulfinch. He had sealed himself away from the clean air and health-giving hills to speculate in sterile futility on the historic journey of T. Allen McQuary. For months Otis had been stacking newspapers on his desk, clipping articles pertinent to his investigation, and pasting the clippings into a massive book. From time to time, he would swivel about in his chair to stick brass thumbtacks into a large map taped to the wall. Some two dozen thumbtacks wound in a serpentine wriggle from the "Show Me" State of Missouri (pronounced with an "ee" not an "ah," as some degenerates would tell you) to the Charleston harbor. Depending on which paper Otis consulted, the Purple Knight of the Ozarks (God, how he hated that title) had set off from Neosho or from Springfield or from Mountain Grove, but after that, the record was less ambiguous: he made his way north to Bolivar, then northeastward to Herrmann, and then due east to St. Louis. When the Purple Knight rode into Decatur, Illinois, he was received like a conquering hero, but in Bement he was despised and rejected and so shook the mud from his purple boots. Subdued and damn near ready to give up, McQuary remounted Rozinante and passed from Illinois into Indiana on his way to Indianapolis, and then on to Richmond and Cambridge City. And then, whaddya know? He was lauded and applauded in Cincinnati and collected some real money. The nave of the church reverberated, the girls swooned and mooned, and he sold 200 booklets at a dime apiece, which he added to the "love offering" for a whopping total of $183.00. So, with his chin up and banners snapping, McQuary rode south to Portsmouth and Ironton and ferried eastward on the Ohio to Ashland, named for the trees and not the detritus, and then to Catlettsburg whence he penetrated deep into Kentucky as he followed the Big Sandy to Pikeville. A pass through Tennessee–Bristol and Johnson City–another pass through North Carolina–Asheville, named for Sam Ashe and not the Yoruban life force—followed by a sweeping traverse across South Carolina that culminated in a riotous lecture at the magnificent Charleston Gold Club. And then . . . and then there was naught but ocean all the way to the horizon.

Thus indicated the map of Otis Bulfinch, and he regarded the map with bitter resentment, an emotion so all-consuming it can only be communicated with a pleonasm (not to be confused with a neoplasm, though pedants consider a pleonasm to be a linguistic neoplasm).

Otis Bulfinch's map tracking the Purple Knight's journey

Why bitter, you ask? Well, for one thing, the journalistic record was sketchy. Otis might read that McQuary spent the night in Bement–wherever in the hell that is–but he surely didn't ride all the way to Indianapolis without stopping along the way. Where did he stay? What did he do? Otis suspected there were women: a couple of the articles suggested as much. But how to prove or disprove dalliances? And if McQuary was exposed as a womanizer, would he be discredited thereby?

Otis had good reason to think not. For it was he who called the bank in Little Rock to speak with Colonel Fletcher, the ostensible auditor who would attest to the validity of the contract, only to learn there was no Colonel Fletcher at all anywhere, at least not in the state of Arkansas. Otis's expose of the Fletcher scandal in the Springfield Leader should have ended McQuary's whole scheme, but for whatever reason, the Purple Knight prevailed and Otis did not.

Furthermore, Otis could not verify that McQuary had made his journey entirely on horseback. Had McQuary cheated and take a train? Probably. But Otis was immobile, feckless, and constrained to reading newspapers in an office, while the Purple Knight was moving, moving, always on the move. Otis thought of himself as the focal point of a pocket watch whereas McQuary was the second hand, but on this watch face, there were neither tick marks along the periphery nor a radial arm between the post and the pointer.

Here's another analogy Otis worked out in his journal:

"Naive truth seekers believe they will confront a Gordian knot of lies. To their dismay, they will immediately learn that the 'knot' metaphor does not hold: Lies are not knots to be untangled or severed. Lies are more like unruly children who run about with their hands over their heads and holler, 'Naa-naah-naah!' to the truth seekers. So, the truth seekers lace their sneakers in preparation for the chase only to find the lies occupy the green sward, and they are calling to their lying friends to join them, and suddenly lies are everywhere, more like a swarm of bees than a game of Capture the Flag. Daunted but determined, the truth seekers take to the field with butterfly nets to catch the lies. Then the truth seekers call out to their friends, 'Hey, you guys! Get your asses over here!' only to find that the truth seekers don't have many friends, not real friends, anyhow. Some of their 'friends' may claim to be on the side of the truth seekers, but they're not. These 'friends' just believe their own particular set of lies–lies they dress up in bright jerseys to run around on the field and knock down the other lies. (A liar who knows he's lying is more honest than a man who believes a lie but insists the lie is true. By claiming certainty, such a man is not only a liar but also a fool.)

Many of the lies, however, do not belong to anyone's team, and they mind their own business. Their feet are wet with dew as they catch twilight fireflies and put them in mason jars. These are the folktales. Night is falling, but the folktales don't 'wanna go to sleep. We don't wanna!' All night long, laughter and songs and drunken stories resound throughout the glade. Meanwhile, the truth seekers have to string up hammocks in the darkling trees and get some rest. Tomorrow is another day.

Those with ears, let them hear: Otis was the truth seeker and McQuary was one of the happy lies, not just a liar but a lie incarnate, a living, moving lie. Indeed, Otis's principal frustration lay in the fact that by the time he read where McQuary lectured, slept, or dallied, McQuary had already departed for somewhere else. Try as he might, Otis could not catch up with the Purple Knight, and what was worse, Otis couldn't anticipate where he would be next.

And that's why Otis Bulfinch glared at the map, slumped back in his chair, gritted his teeth, seized a half-empty cup of coffee off a stack of papers, and hurled it against the map. A massive splatter of brown soaked the southeastern United States, and dribbles of coffee ran down the wall to pool at the lip of the baseboard. In a mystery of physics, the cup thumped hard, rebounded, fell unbroken to the wood floor, and rolled under the desk. Otis swiveled around and put his hands on his desk.

Why do I even care? Why?

He found the cup with his foot and side-kicked it from under his desk.

I'll get it later. Doesn't matter anyhow. Goddamn cup.

An old despondency descended on Otis Bulfinch: The melancholy attending his vain pursuit merged into frigid February as the sun declined to a magenta strip over a bristling hill to recapitulate the uncertainty of all human endeavors. Otis took a newspaper from his desk, popped it open, and looked for the obituaries, for he had long ago discovered that the death of others is the strongest antidote to melancholy. He searched the paper until he read the following article:

Linn County Budget-Gazette, Saturday, Feb. 19, 1898, p. 1.

Linn County Budget-Gazette . . . I wonder where the hell Linn County is? I think St. Joe is in Buchanan County, so I guess Linn County must be close. I never heard of the Budget-Gazette. Or Burlington Junction. Or Nodaway County either, for that matter.

Looks like the humongous Mrs. McBride nodded away once and for all.

Ha.

They probably buried her in a piano crate, and now the good folks of Linn County are having a good laugh at her expanse.

Everybody turns into a cartoon after they die, at least potentially. And why not? The dead don't know the difference, so no harm, no foul.

Oh, oh! Here's an idea for a cartoon: A couple of laughing unicorns are sitting on Morris chairs with drinks, and the caption reads, "Two unicorns mock the fate of non-existence."

Two unicorns mock the fate of non-existence.

Wonder who I could get to illustrate it?

Succumbing to sadness and ontological despair, Bulfinch closed his eyes. His hands, still clutching the paper, slumped onto his stomach. He was declining into the "trough of the afternoon," that dull duration between four and five o'clock when mind and melancholy yearn to sleep while our bosses demand we work. Otis had learned over time to position the paper so that anyone looking through the window of his office would think that he was reading. He had stolen many helpful naps that way.

Consciousness had all but ebbed when he noticed an uncanny incandescence beginning to glow behind the Linn County Budget-Gazette: radiant beams stretched upward as if a little sun were rising. Bulfinch watched in fascination as the glow ascended, and he gripped the edges of the paper so tightly that it stood stiff and did not quiver. Something or someone had intruded into his office and waning consciousness, and the only thing between Otis and sheer terror was the paper in his hands.

And still, the globe rose inexorably with inexplicable purpose.

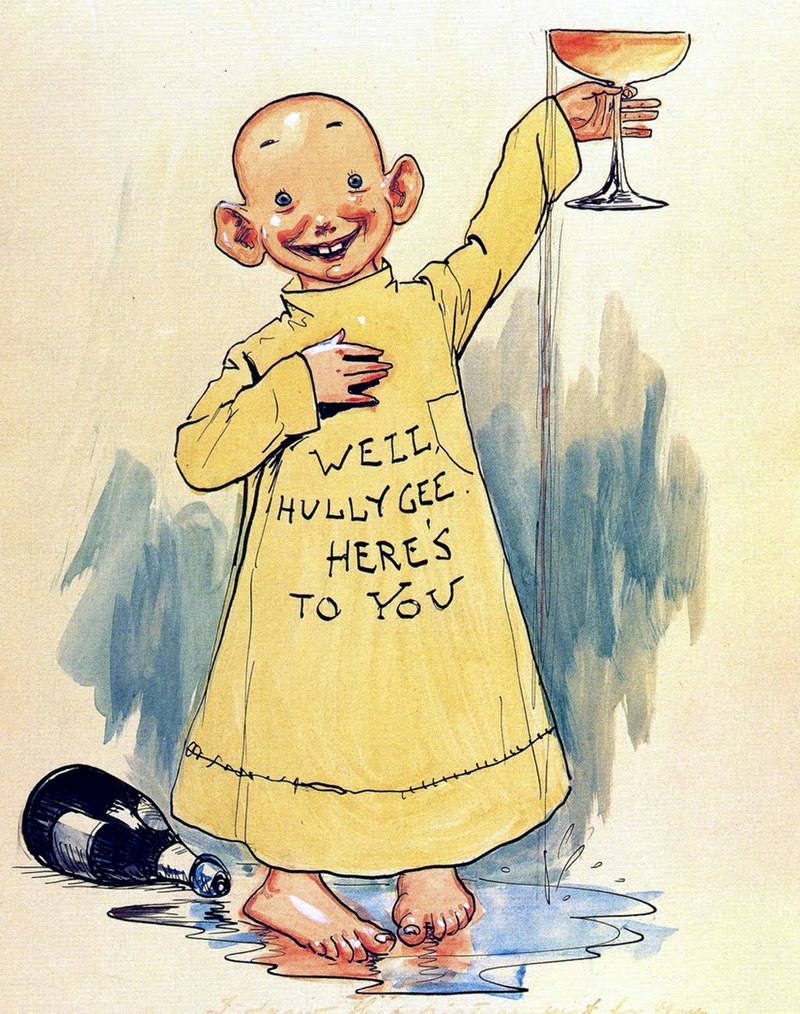

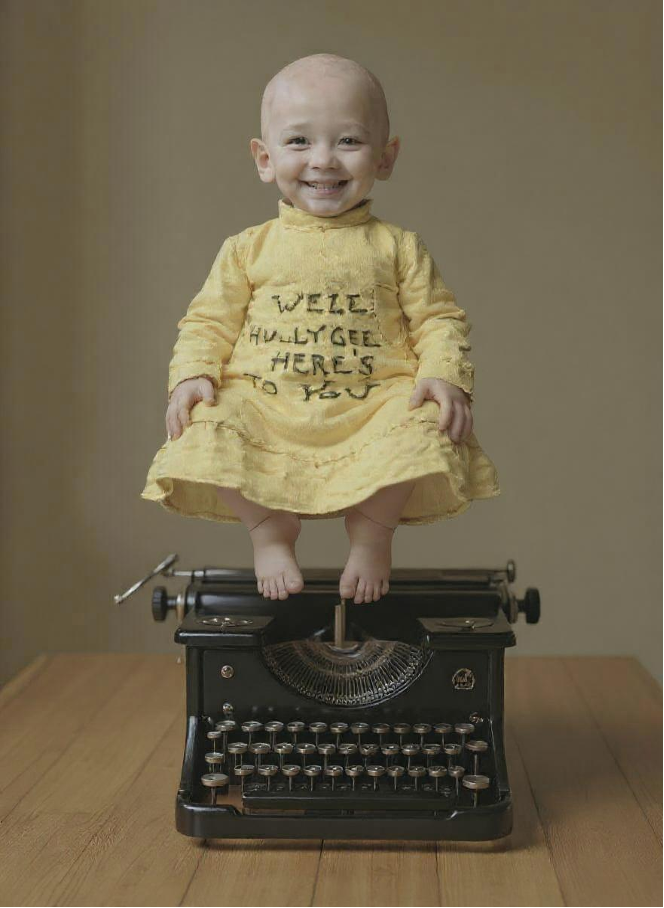

Round and gourd-like and shining, a peach-yellow orb emerged into Being from the piano crate of Mary McBride in the Linn County Budget-Gazette. Eyebrows followed, little hyphens way up on the forehead, and then flapping ears that protruded from the head and, finally, two empty eyes, merry and mischievous and dead. Transfixed with fear but moved by curiosity, Otis swallowed dry spit and lowered the newspaper. An apparition hovered over his typewriter: a cartoon boy not quite four feet in height with a bald head and a yellow nightshirt. He was grinning a gap-toothed, disturbing smile. The globular head and merry, dead eyes and rictus grin lent the child a horrifying aspect unalleviated by his peach-yellow nightshirt.

The Yellow Kid appears

Otis whispered, "What are you?"

The boy in yellow chortled like an opiated cherub and spread his arms. "Low and bee-hole and Hully-Gee: I'm the answer to your prayers to Almighty Truth, thass who! And don't act like you don't know who I am! Ever'body knows Mikkey Dugan, the most best seller of newspapers ever there was, Mr. Poolitzer's boon and bosom buddy, the toast of New York Shitty, the apple of Mr. Hearst's wandering eye, the Yeller Kid!"

A pirouette and a bounce, and the cartoon-boy floated above the Royal. "Here'za story for youse. Did you know I busted fully yeller from the head of my poppa, that's Mr. Outcault to you, and Hully Gee, here I is, at your service!" The boy bowed.

Otis whispered again, "What in the hell? It can't be..."

The boy cupped his hand around his mouth and replied in a mock whisper, "Seems the only feller in hell is you."

"You're not real."

"Not real? How can a cute little feller like me, the most popular kid in the World not to mention the St. Looey Post-Dispatch, not be real? Fat lady McBride, who died in Nodaway County and is buried out by the compost heap, ain't real. She's dead and gone, rotten and forgotten, more fake than fact. But me? I'm more real than everybuddy and a ton more real than anybody in the graveyard–well, except maybe Dracula, that old Inksucker!"

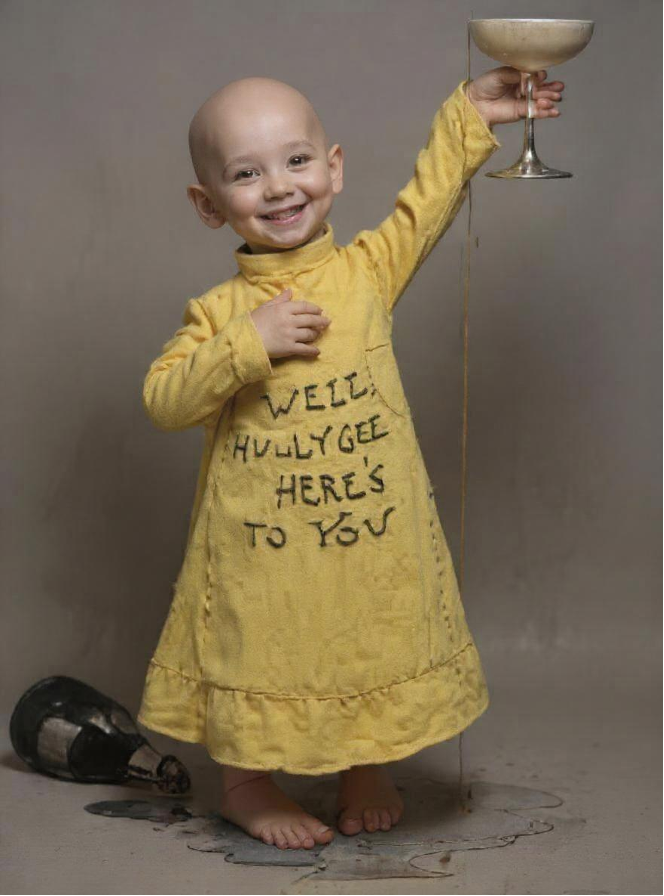

The Yellow Kid

The boy floated forward until he hovered only a few inches from Bulfinch's face. "Lissen to me! Jest lissen! I'm more real than that Purple Feller you er so crazy about findin'. And that's why Almighty Truth sent me! The Truth said to me, 'Lissen hear, Mikkey Dugan, the only way to beat one cartoon is with a better cartoon, and yore the best gol-durned cartoon in the whole world. Ipso facto, I'm a-sending you to Mr. Outis Bullshit! Almighty Truth said it, not me, so it's gotta be true.

"Have you seen this, Mr. Bullshit? It's a picture of the Purple Feller as a cartoon." The Yellow Kid reached into his left sleeve and produced a familiar illustration.

The Purple Knight as a cartoon

Otis glanced at his office window, not the exterior window that looked out on the magenta sun now sinking into a deep orange, but the interior window that looked out on the desks of the copy editors and accountants. The room was nearly empty, but Doris from the steno pool was watching him with pursed lips as she gathered her coat and purse to leave. He smiled at her and waved, and she returned the fake smile all people give when they've been caught staring. Otis heard Dobbins whistling somewhere toward the front of the building, and above him, the heavy thumping of the presses was slowing into lassitude and finally silence. He checked his watch: ten to five. The floating boy was hovering over the Royal on his desk and smiling a vacant, uncanny smile. Otis stood abruptly, walked to the window, and twisted the rod that closed the blinds. He locked the door. He hung up his coat and loosened his necktie. He stroked his mustache. He paced across the office and opened the outside window and leaned out to inhale the clean, frigid air. And all the while, the Yellow Kid watched him with a slow pivoting rotation of his gourd-like head, rather like a lighthouse tracking the progress of a foundering ship. Bulfinch sat back in his chair, clenched his fists, and hissed at the cartoon boy, "You are not real."

A chortle and a chuckle and a chipper ha-ha. "You keep sayin' that! You're the one what ain't real! Listen, hear, Otiose Bullshit, you is less real than the Purple Feller and a helluva lot less real than me! You are a pigment of your own imagimanation!"

The Yellow Kid at the typewriter

Bulfinch looked at the boy and thought, This can't be.

A chortle and a chuckle and a chipper heh-heh. "Otiose Outis, not only can I be, but now that I am, I gotta be. I'm what they call 'inevitabubble.' I was sent to help with your conundrummin'!" The Yellow Kid patted his hands on an invisible bongo. "See?" He patted his hands in the air.

Otis dragged the trash can between his legs and vomited. When he looked up, the Yellow Kid was still floating above his typewriter and grinning.

"Oh, my God–"

"Yore God? Yore God? What about my God? Nobody ever thinks about my God! A cartoon World has gotta have a cartoon God. It only stands to reezun!"

Otis whispered, "Why are you here?"

In a sing-song voice, the Yellow Kid answered, "Somebuddy sent me; don't resent me! And ol' Somebuddy cares about the Truth even more'n you. Thass who sent me."

The Yellow Kid began floating forward again, and Otis held up his hands as if to fend off the apparition.

"No, no, please stay away! Please!"

Don't lose your wits, Otis. Breathe.

"That's right, Outis, don't lose none of them wits of yours. You ain't got many to spare! Heh-heh. You want to breathe, so breathe, and it'll be alright."

"I'm breathing."

"Good. Now listen." The Yellow Kid sat criss-cross applesauce above the typewriter and floated in mid-air like a New Delhi guru. He tugged his night shirt over his shins and said, "Otiose, your problem is one of transportification. How ken a settin' man ketch a movin' man? Not by readin' the oh-bitch-iaries, that's fer sure!" The Yellow Kid chortled, and his head bounced up and down on his shoulders. "No, you'd be way better off if you was in the funny papers."

"If I were in the funny papers?"

"Yessir! Then you could be like me and climb right inside that Purple Feller's head."

Breathe, Otis.

"That's right, Outis. You just keep breathin' and let me do the splainin'." He reached inside his sleeve and took out a thick scroll. "Here ya go. Open it up." Otis took the scroll from the Yellow Kid and rubbed his thumb along the fraying tightly rolled end. He wriggled the scroll like a baton and felt its heft. He felt the mottled texture of the parchment in his palm. Then Bulfinch untied the ribbon and unrolled the scroll, and there at the top of the scroll in Clarendon two-inch bold typeface was a headline: Otis Bulfinch Exposes the Purple Knight of Missouri. Then, in smaller print below: Famed reporter sacrifices everything for the truth. Wealth, status, and girls are his for the asking.

Otis asked in a low voice, "Where did you get this?"

"From the gettin' place, where else? From ol' Somebuddy." The Yellow Kid rolled on his side and stretched out his legs until he reclined in mid-air with his hand under his head, rather like a Gibson girl taking her ease on a settee. "Read what the paper sez. Somebuddy told me to tell you it's a 'binding contract.'"

Otis Bulfinch read the "why's and wherefore's" and interminable clauses whose pronouns referred to unclear antecedents, and the dreamlike sentences kept altering their style from legalese to journalese to opinion-ese to gossip-ese to commercial-ese to comic-ese and back to legalese, over and over, rather like Proteus, stinking of seal funk and brine. The upshot of the contract was–

"Upshot? Why in the world does you call it an upshot?" The Yellow Kid chortled. "Makes no sense. What is an 'upshot' anyhow?"

Otis did not know, but the upshot was that if he signed the contract with the Yellow Kid, he would be enabled (by Somebuddy, whoever that was) to pursue McQuary via occult and magical means, so that, eventually Otis would unmask McQuary as a fraud and expose him to the world. Shortly thereafter, M.S. Glenn would also be exposed, imprisoned, and ruined. Furthermore, the contract promised that all evil-doers and frauds and fakes and liars would stand naked in the stark light of day, and the Almighty Truth would rise skyward like a magnificent sun, or better yet, like an All-Seeing Eye atop a pyramid, the Eye that never sleeps nor does it slumber.

The contract stated in no uncertain terms: All Truth Seekers everywhere will indububbly catch all the lies on earth in butterfly nets, and the Truth Seekers will put the lies in mason jars where they will blink forever with a weak chartreuse glow, harmless and no more entertaining than an aquarium of guppies.

Otis looked at the Yellow Kid and asked, "And all I have to do is sign at the bottom?"

"Thass all you gotta do!"

Bulfinch pushed his spectacles to the bridge of his nose and began curling his mustache again. He pinched his lower lip and thought, This is crazy.

"No, Mister Bullshit, sir, this ain't crazy at all. I'm the sanest cartoon boy who ever was because I know I wasn't and ain't and never will be, and that don't bother me one whit."

"And what happens if I don't sign?"

"You'll set behind this here desk and throw coffee cups at the wall and wish deep down you was MacQuacky and MacQuacky was you. I'm a-gonna show you sumthin', but you gotta close your eyes. That's right. Close 'em. Here we go."

Bulfinch closed his eyes, and almost immediately, the Purple Knight rode a black horse onto the stage of Otis's imagination. The Knight entered from the left, smirking and waving, while pretty girls in the front row said, "Ahh," and "Ooh," and combed out their hair. When the Knight reached center stage, he wheeled Rozinante about to face the audience. The Knight was wearing a purple mask and his plume was magnificent. In the middle row of the theater, Otis was sitting with a pencil and pad on his knee. His brows were furrowed, and he began scribbling angrily on the pad, whereupon the Purple Knight laughed and Rozinante whinnied and nodded her head. Then the Knight reined the horse to exit to the right, and Roz swished her tail to bid Otis an indifferent farewell. The stage, however, remained empty for only a moment, when once again the nose of Rozinante appeared on the left and the whole charade began again.

Otis opened his eyes, and the Yellow Kid was still reclining in mid-air. "Well?" he asked.

Otis Bulfinch asked, "Where do I sign?"

"By the 'X'. Right der by de 'X.' See you in the funny papers!"